Alaska News Brief November 2024. Giving knits the world together

By Chase Hensel, board chair

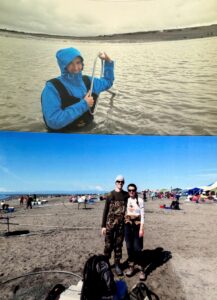

I was staying with friends in a coastal Kuskokwim Delta village, researching the effects of their Community Development Quota fishing share on the local economy. Walking back on an elevated walkway at lunch time, my hosts’ next-door neighbor, Angilan, came out of her house to invite me to lunch.

Later, she said she knew that my friends were both working at the school and worried that there would be no one at home to offer me food. We had chum salmon that she had dried and smoked, pulling pieces of dark, red meat off the skin, and dipping them in salted seal oil. The chums, caught by drift netting on the ocean and dried in the cool salt air of the coast, were rich and tangy. Afterwards, we drank tea and ate akutaq (Yup’ik ‘ice-cream’). The akutaq was extravagant with salmonberries and crowberries.

Chase and Phyllis Morrow on the lower Johnson River near Kasigluk, 1977. Photo by Jim Hensel

We talked about fishing. I was surprised to learn that this far south, when the wind blew inshore, they sometimes caught Yukon-bound king salmon. Those kings were already following the scent of their home stream as the wind pushed the river water along the coast. She told me that the Yukon kings were easily recognizable; they were much fatter than Kuskokwim kings. For that reason, they made the best egamaarluk (half-dried fish). She said she would invite me over the next time she cooked some. It was magnificent: lightly smoky, its flavored intensified by the drying, but with a texture more like cooked fish than fully dried fish. It was as rich as a marbled steak.

I thanked Angilan and sometime later sent her an ipuun – a wooden serving spoon traditionally used to serve akutaq – that I had carved. Twenty years later, her kindness stands as a marker for me as to how we should treat each other and our world.

A major reason I became a Trustees board member was to protect subsistence rights and subsistence resource usage. This is one of the superpowers of Trustees’ able lawyers—going to court to uphold the laws that protect water and air, the land, and the ways of life of Alaskans now and for generations to come

Angilan and all those who rely on Alaska’s resources should continue to have fish to catch, process and share in the future.

The tens of millions of salmon that return to Bristol Bay support the world’s largest sockeye fishery and provide tremendous environmental and economic vitality to the whole region. They are also the lifeblood of the people who live there. When enormous projects, like the proposed Pebble mine garner political backing and momentum, legal strategies and public support are the essential counterforce.

I have been hosted and fed on Bristol Bay sockeye salmon in Dillingham and New Stuyahok, and Manakotak and Togiak. On visits to Nelson Island and along the Kuskokwim and the Yukon, and in Utqiagvik and Kotzebue, too, I have been invited into countless Alaska Native homes and fed from the gifts of the ocean, rivers, and land.

Stephen Qacung Blanchett as a boy with Chase in Nunapitchuk over 45 years ago. Photo by Phyllis Morrow.

Gifts are invaluable. All that kindness, hospitality, wonderful meals, and comradeship inspires me to support Trustees. I want those fish, that game, those birds to be caught, processed and shared in an ongoing cycle. Giving knits the world together.

Trustees for Alaska has been a major force to protect Alaska’s environment for the past 50 years. Salmon and other fish need protection from industrial operations like stream dredging, from mining spills and runoff and the collapse of dams holding toxic mining waste. Salmon need clean rivers on the long journey to the sea and back.

Trustees has been the pivotal legal team stopping massive mining projects like the proposed Pebble mine. Such projects potentially threaten land, lives, and livelihood.

Trustees’ lawyers have also successfully fought against enormous coal mines near the village of Tyonek which would not only have potentially destroyed 20 miles of salmon streams, but pumped masses of carbon emissions into the air.

Against what sometimes seem like impossible odds, Trustees has worked to protect the nursing and birthing grounds of the Porcupine caribou in the Arctic Refuge from oil and gas extraction.

Each of us needs to do our part to protect the environment. If there’s a buck to be made tearing up the Earth, someone is ready to do it. I’m proud to add my bucks to the countervailing force that keeps communities and ecosystems a priority when industrial projects are proposed.

This is why I have given and will continue to give time and money to help Trustees move into its the next 50 years. I serve on the board and as board chair, donate every year, and have included Trustees in my will.

The small gift I sent to Angilan was enough—and not nearly enough—to express my thanks. Giving to Trustees spreads that gratitude. What a pleasure to be able to pay it back and forward at the same time

-Chase Hensel, Board Chair

PS. Thanks to supporters like you, we can continue fighting to protect Alaska’s land, water, air, wildlife and people.

The fifth decade: Goodbye coal, hello chaos (and winning)

Drinks with lawyers–Siobhon peers through the looking glass

Attorney Michelle Sinnott is back–and still “Into the Wild”

We did so much good work together the last 50 years, let’s celebrate! Trustees turns 50 on Dec. 16 and would love for you to come join us for food, drinks, stories, and a big bear hug for our collective love of Alaska the last 50 years and for our love for Alaska in the 50 years to come.