On why making a will is kindness

By Dawnell Smith

When someone dies, someone else grapples with their stuff. They make decisions about treasured belongings, keepsakes, collections, journals, letters, bikes, cars, and other objects, and also about accounts and homes, whether a few hundred bucks in a savings account or an IRA and a beach house or remote cabin.

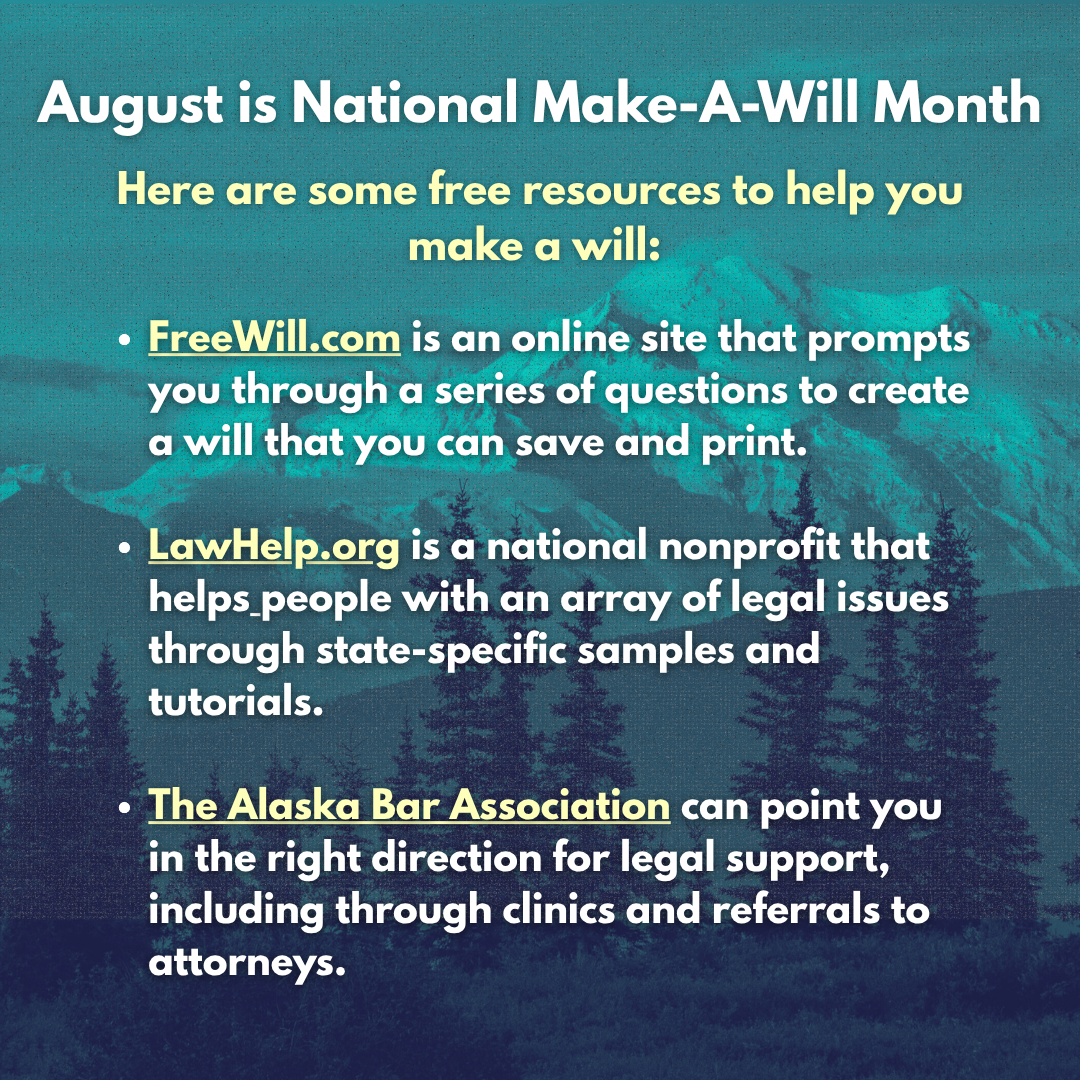

Visit some of these free resources to help you make a will!

I’ve learned a lot about this process over the past five years, and I’ve witnessed others do the same. I now understand that a will is not just a legal document with instructions, but also an act of kindness and a guide that helps people do the right things at the worst of times.

Making a will helps you think through what matters to you, and thoughtfully pay your life forward. You can pass things on to family members and friends in general ways, and make specific choices that mean something to you—like giving that book collection to the bibliophile in your life, or that legendary old canoe to the niece who spends all her free time on the water, or passing part of an IRA to a charity you support.

A will can prevent misunderstandings and disputes by providing clear guidance to the people who come after you.

I don’t have kids or much stuff. Why do I need to make a will?

A whole lot of people don’t think about making a will until they have kids or get to a stage of life where other people start asking about it. Some people don’t have the kind of things they think belong in wills, like a home or a chunk of money. But consider making a will as less about distributing things with monetary value and more about the values you hold.

In other words, make a will because it will bring clarity to those values for those who come after you, and it will make the process easier too.

In other words, make a will because it will bring clarity to those values for those who come after you, and it will make the process easier too.

Back in 2020, my older brother died unexpectedly after a short period of feeling sick and my mother was his heir. It took well over a year for her to access his small bit of savings and transfer title to his car to a family member. She was able to push through a more simplified probate process to do it because what he had was below a certain monetary value, but not without an emotional burden.

The cost to her came in waves—the frustration, the confusion over paperwork and processes, her financial need as a person on a fixed income trying to cover the cost of a funeral, and the repeated cycles of grief. My other brother and I had her back, of course, but that didn’t reduce the strain.

My older brother didn’t have a lot of stuff—beyond a huge collection of albums now shared among family members—and he wasn’t married and didn’t have kids, so it never occurred to him to write a will. He sure didn’t think about it when sick those few weeks either.

That convoluted multi-state probate thing

Sometimes the lack of a will can incur generational costs. Kids, grandkids, nephews, nieces, friends and others can absorb the financial and emotional costs of legal processes, of storing or shipping objects and documents they don’t know what to do with, or having to hire people to track down distant heirs. Sometimes heirs don’t know about an inheritance at all.

When my dad died of cancer in 1983, he didn’t have a will. My mom’s name was on the few things they owned together, so they never thought about it. Fast forward 40 years, my mom in her 80s by then, and we learned that she had inherited by law a third share of a piece of land my dad’s parents had bought long before he died.

Turns out, someone wanted to buy that land, which had turned into a tax nuisance of sorts anyway, so the grandkids of the original purchasers had to figure out and then undergo a multi-state legal process to confirm them as heirs via intestate succession laws.

Turns out, someone wanted to buy that land, which had turned into a tax nuisance of sorts anyway, so the grandkids of the original purchasers had to figure out and then undergo a multi-state legal process to confirm them as heirs via intestate succession laws.

If the words “intestate succession” sounds like something expensive and painfully slow—because it absolutely is—then by all means do everything to avoid it or anything like it. Make a will. Ask the people you know to make a will. Get those wills signed and share them with people. The old “surprise or secret will” thing may play well on TV, but that’s not usually the kind of drama you want.

My mom died before that legal process played out and that land sale could go through. She had looked forward to paying off debt, giving the grandkids a little something, and enjoying a small financial cushion for a change. My other brother and I stepped in to give and “loan” her money, of course, but she sure didn’t like that at all.

Sometimes when we learn things the hard way, it’s not because we didn’t get to something we should have, but because we didn’t know something or have access to the information or resources for knowing those things.

Oh, the lessons we’ve learned

Lesson learned. I made a will about ten years ago and revised it in April. I updated all my beneficiary forms as well, where I included Trustees for Alaska and a few other nonprofits.

Beneficiary designations on life insurance policies, retirement accounts, and payable-on-death bank accounts typically override the instructions in a will, bypass probate and require a transfer directly to the beneficiaries. Making a will that aligns with these beneficiary designations is important, though, to avoid confusion and disputes.

Every person’s situation calls for different things when we’re planning for what happens to our stuff when we die. It starts with making a will.

I may not have a lot of money or valuable things to pass forward, but I made a will to give clarity to whoever grapples with my stuff. I made a will to show care to my values, to those I love, to all that matters to me.

I guess you can say I’ve learned that a will is one way I can keep showing kindness when I’m gone.