Stay here and fight, stay here and dance

By Christin Swearingen

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” -Margaret Mead

Christin with alpine jelly cone fungus in her hat. Photo by Karlin Swearingen.

In the middle of the COVID pandemic, I faced a choice. I had been accepted to a PhD program at University of British Columbia with a wonderful advisor, Dr. Mary Berbee—one of the best fungal taxonomists in the region—but I had also just heard back about a conservation coordinator job with Interior Alaska Land Trust in Fairbanks.

Mushrooms delighted me, but I could not ignore climate change and the need for action. Forests keep burning beyond past norms and fewer beluga whales show up in Cook Inlet every year.

Plus, moving to Vancouver during the COVID restrictions was going to be logistically challenging. It was the first Trump term, and I kept repeating a catchy song in my head:

Don’t move to Canada, don’t move to France

Stay here and fight, stay here and dance.

Don’t move to Canada, that won’t change a thing,

Stay here and fight. Stay here and sing!

Feeling the heat

And so I stayed. There is so much still to learn about fungi, but what good is it to discover a new species if it goes extinct? How many species have gone extinct without us even knowing they existed?

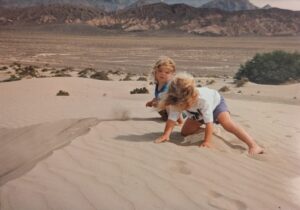

Christin and her sister playing in the sand of Death Valley National Park. Photo by Margaret Anderson.

I have cared about questions like these since childhood. My parents are both National Park Service rangers. We lived in Death Valley National Park in California when I was a kid. My sister and I had the entire 3.19 million acres to explore and play in, as long as we had our water bottles, hats, and common sense.

We mostly played in the hills right across the street, our range limited by extreme heat. In many ways, the sub-zero winters in Fairbanks feel very much the same. You know the feeling when you open a preheated oven and the air blasts your face? That’s kind of like biking at 120 degrees or -40 degrees Fahrenheit.

Land of extremes

In Death Valley I grew a deep appreciation for every living thing since each shrub and fleeting wildflower offset each other by a stretch of sand and sun-lacquered rock.

Christin with the rainforest restoration crew in American Samoa. Photo courtesy of Christin Swearingen.

When I was 12 my dad faced a career choice, and I was told we were moving to either American Samoa or Alaska. I remember saying I didn’t want to move to American Samoa because I didn’t like coconut. I had no idea what Alaskans ate.

We ended up moving to Anchorage, and I was happy to find plentiful blueberries, salmon, and wild mushrooms. (In a poetic turn, my family did end up having a short stint in American Samoa when I was 17, and I discovered I actually did like coconut while working a rainforest restoration summer job while there).

Eventually I double majored in biology and environmental studies at Oberlin College in Ohio. My sister and I both applied to master’s programs together and ended up at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, where we both studied natural resources management, but with very different thesis projects.

The community of Fairbanks welcomed me immediately. I went contra dancing with friends, invited people to my dry cabin for hot soup and board games, and got involved with the Fairbanks Climate Action Coalition to push for a borough climate action plan. We succeeded several years ago.

I met my husband, Karlin, at a contra dance camp (he was the lifeguard…long story for another day). After my sister and I graduated with master’s degrees, Karlin and I moved to Anchorage where he worked as an environmental engineer, and I took several jobs, including as a marine mammal observer at the port of Anchorage, bearing witness to the decline of the beluga. That’s where I faced that choice between getting a PhD or doing conservation work, going to Canada or heading to Fairbanks.

This delightful world

Boletus mushroom found by Christin. Photo courtesy of Christin Swearingen.

Sitting against an old-growth spruce tree one cool fall day, breathing in the senescing cranberries and labrador tea, I noticed puffs of smoke here and there as raindrops tapped on puffballs, releasing spores into the air. I thought, “this is what I want to protect.”

This boreal forest, the Mojave wildflowers, the Samoan fruit bats… this delightful world within which to be alive. I’m committed to doing my best to keep nature thriving forever, and now I’m doing that with Trustees.