The fifth decade—goodbye coal, hello chaos

in 50th anniversary, America's Arctic, Bristol Bay, Litigation, News, Wild Lands & Wildlife

By Dawnell Smith

The last decade feels like a dust storm—like a blur of chaos caused and fueled by propaganda and disinformation, political lies, and volatility, and of course the wildfires and storms that have lived up to decades-old predictions about how climate change will impact our lives and communities.

Trustees crew in December 2021 on a cold but beautiful, clear day. Photo by Ohara Shipe.

The storm may be what we remember first, but what we remember most is navigating through that storm with so many others, and coming out of it knowing we held ground, we held off coal, mining, and oil and gas projects, and we held fast to our mission of protecting places in Alaska that nourish so much abundance.

In our first decade we faced off with Alaska broadcasters who thwarted fairness in the airwaves by pushing anti-environmentalist views on the news and refusing to share Alaska voices calling for protecting the land. Today, we face a media landscape where billionaires behind the curtain push their agendas by targeting their propaganda at different people in different ways to sow fear and anger.

Yet still the stories of people in community matter. Alaskans who stand up for their homes and homelands cover thousands of miles to talk with decision-makers; to speak up at town halls; to write letters to editors and join Zoom calls; to gather in solidarity and protest.

This has steadied us all along the way. People coming together for each other and for future generations. People uniting on behalf of animals and natural places. People demanding climate action and the right to live in a world where we don’t sacrifice the health and life of others to enrich a few. People donating, showing up, staying engaged.

Just as the challenges of the past tumble into the future, so do the lessons. We’ve spent the last 50 years doing our part to head off extractive projects that would enrich a few, while devastating and polluting the land, water, and air that the rest of Earth’s living beings rely on for life, tradition, and connection. We began our fifth decade in 2014 knowing the playing field. The legal work has changed; it has gotten harder. Political and corporate strategies to skirt or disrupt existing laws and processes, including bedrock environmental laws meant to protect us, have altered the legal landscape.

Celebrating the protection of brown bears by climbing Bear Mountain in the Kenai Refuge with folks from the Alaska Wildlife Alliance, 2022. Photo by Bradley Pizzimenti

Yet through it all, we worked with others who remained disciplined and united in stopping projects and rules that would exploit Alaska. What gave us hope and strength then is what gives us hope and strength now—people working together. Because in the end, that work is a resounding celebration of this place’s remarkable abundance.

That’s worth fighting for; and so, we did, and so will we do.

It begins with an Arctic win

One of this decade’s themes centered on how the State of Alaska and others would drum up novel, wasteful and legally dubious theories to disrupt established interpretations of the law, at great expense to taxpayers, said Vicki Clark, executive director with Trustees. This meant that “accepted legal issues that everyone had understood were not open to interpretation were suddenly in play.”

One case centered on the Interior Department’s denial of a State of Alaska application to do risky and destructive oil and gas exploration in the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. At the time, the Arctic Refuge was still closed to all oil and gas and the State had no business proposing a seismic program that would have cost the state tens of millions of dollars. Despite that, the State sued Interior in 2014.

Caribou in the Arctic Refuge. Photo by Florian Schulz.

Representing the Gwich’in Steering Committee and eight allied groups and working with co-counsel Bessenyey & Van Tuyn, LLC and the Natural Resources Defense Council, we won that case — making it clear that the State had no grounds for pushing oil and gas activities in the Arctic Refuge.

The effort to bend the courts and law to the will of political agendas got bolder as the decade progressed, but we were there every step of the way to hold the line on the law. Once the Trump administration came into office in 2017, it dished out a slew of hasty, poorly reasoned decisions to give away public lands and authorize industrial projects. The administration put up an “Alaska for sale” sign.

Our job involved putting up a steadfast legal defense and being a diligent watchdog. Our lawyers spent many long weeks, weekends, and nights writing hundreds and hundreds of pages of legal arguments, vigilantly tracking federal actions and processes, and laying the legal groundwork for challenging decisions and actions already underway and coming down the “drill, baby, drill” conveyer belt.

Even as we felt the weight of the work and how it would resonate in the years ahead, we also had cause to lift our heads up and celebrate, because good things happened this decade—like the end of coal in Alaska.

Winning in 30 words or less

Brian Litmans remembers how the coal industry’s effort to entrench the sector in Alaska ended—and also how it began.

“Something I had not really seen in my career were the ways in which organizations were coming together, national to state to community groups, with knowledge, passion, interest and a recognition that it wasn’t just their fight, but that they were part of something bigger,” said Litmans, who worked for over 15 years with Trustees as attorney, senior staff attorney, and legal director. “And that required a campaign not just for one project but rather for any threat that would allow the coal industry to get that proverbial foothold in the state.”

Some of the people Trustees worked with to protect the Chuitna River in the fourth decade and who helped create the cohesion and unity for stopping the mine in Trustees’ fifth decade. Photo by Brian Litmans, 2009

The proposed Chuitna coal mine helped build this cohesion. The PacRim Coal project would have put a mine 45 miles southwest of Anchorage near the communities of Tyonek and Beluga in upper Cook Inlet, threatening salmon along the Chuitna River and beluga whales in Cook Inlet.

Trustees presented a first-of-its-kind petition on behalf of conservation groups and local citizens in 2007 requesting that Alaska’s Department of Natural Resources designate all lands within the Chuitna River watershed unsuitable for surface coal mining. This effort meant Trustees brought on independent and renowned scientists and experts who could weigh in on the impacts the mine would have on water, fish, beluga whales, climate, and people. Soon after, Trustees went to court in 2008 to challenge the agency’s refusal to consider this petition.

The legal work in our fourth decade helped transform how Trustees and our clients approach litigation into the fifth decade and beyond.

“With Chuitna, we got ahead of the curve in how we worked with experts,” said Litmans. “We brought on hydrologists, economists, wetlands experts, and so on, and that really helped us get more strategic about the role of science in our work.”

That coupling of independent science and expertise with our legal work helped put important data, research, and knowledge into the record, strengthening our arguments in court and helping us write comments to agencies unable or unwilling to put resources into bringing the best science forward.

Working with scientists has propelled Trustees’ work across issues, from mining to oil and gas to how animals like bears and wolves are hunted on federal lands in Alaska. By our fifth decade, those efforts paid off in our coal work.

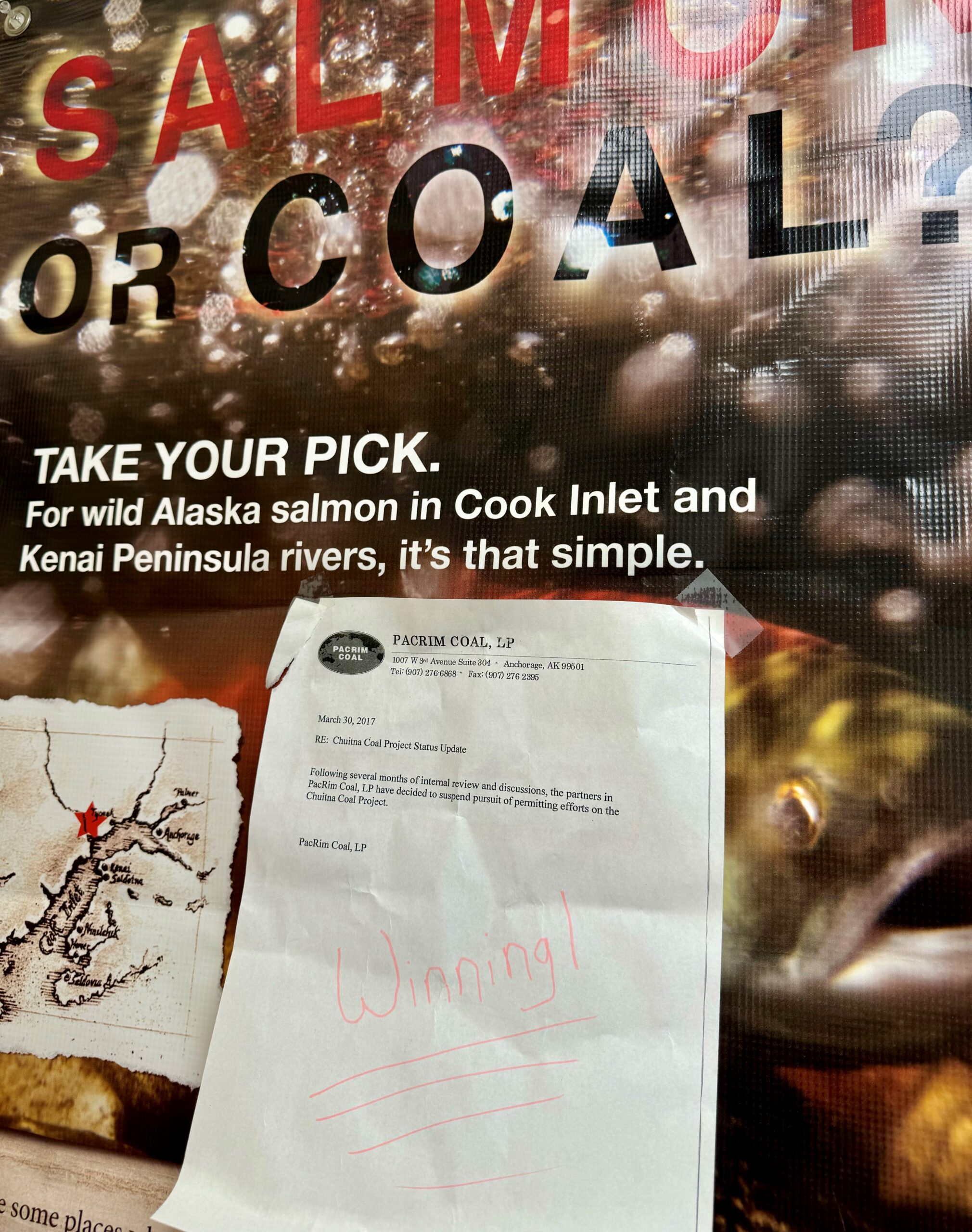

A Chuitna Citizens Coalition Poster with a printout of PacRim Coal’s email saying it would stop trying to permit its coal mine proposal. Photo by Dawnell

“We helped stop one of the biggest coal proposals in the country,” said Litmans. “We kept a new coal mine from getting traction in the Matanuska-Susitna Valley. We stopped and precluded the transportation networks necessary to move coal, and we moved to bring existing coal power to an end or at least require better technology to reduce emissions to benefit the Healy area and climate. We were across the board successful to keep the coal industry from being a part of the Alaska exploitation sector.”

What does winning really look like? With Chuitna, it looked like an email with less than 30 words from PacRim Coal on March 30, 2017:

Following several months of internal review and discussions, the partners in PacRim Coal, LP have decided to suspend pursuit of permitting efforts on the Chuitna Coal Project.

You have to outlast the economics

“Legal successes aren’t always permanent,” said Vicki Clark, executive director at Trustees. “You have to outlive the economics of the project.”

In other words, as long as someone profits from digging, drilling, and sacrificing things like clean water and the health of living beings to boost their pocketbooks and power, projects will continue to churn. Lawyers and clients alike need to commit to years if not lifetimes opposing industries with unbelievable amounts of money and influence. You have to stay vigilant—a longtime Trustees’ specialty.

The work, in turn, requires supporting the people doing it.

Valerie Brown, who came to Trustees as an intern in the mid-1990s and then served as an attorney in two stints, finishing her last as legal director in June 2020, said that one of Trustees’ successes in the fifth decade was internal. The organization focused less on top-down decision making and more on collaboration, and on making the work sustainable for the people doing it.

“Turnover has to do with that internal process,” Brown said. “If you’re an environmental lawyer and could do nothing but write briefs and save the whales, then you would never leave your job.”

Trustees attorneys Valerie, Suzanne, and Brook in front of “The Four Justices” portrait at the Smithsonian in 2020.

Turnover slowed dramatically during the fifth decade and experience increased. Brown remembered four attorneys in the 2000s, with the most experienced only ten years into a legal career. Now, every single attorney except the legal fellows has 11 or more years of lawyering behind them, some closer to 20 years. The Trustees team now has ten attorneys, including the two fellows and the legal and executive directors.

The work environment fostered experience and resilience, and that made an enormous difference in how Trustees responded to the decade’s challenges. The winter of 2017 was coming , and we were prepared.

Winter is here

Attorney Bridget Psarianos joined Trustees in November 2017. She jumped ship from federal agencies based in Alaska after six years because she knew those government jobs would turn sour. Her transition and early period with Trustees was an exciting and confusing time, she said, with an infinite ocean of work and no end in sight.

“If I’m going to have to be wallowing in too much work, I’m glad it’s on the positive side,” she said, adding that those years were horrible with all the work and destructive decisions coming out of the Trump administration, but it was also kind of a fun time, “because we’ve got a great team, I had supervisors who had my back, and we were getting the work done.”

Psarianos came to Trustees with institutional knowledge about Arctic projects, so she ended up on the Arctic team. “Trump was the worst president we’ve had in terms of our work,” she said. “It was an interesting time to jump onto the team when everything hit the fan and would continue to for years.”

She gained experience as a litigating lawyer, too, when assisting two other attorneys on a legal challenge concerning a land swap deal aimed at putting a road in Izembek National Wildlife Refuge.

Clouds and color from the setting sun reflect in the calm water of Izembek Lagoon. Photo by Lisa Hupp, USFWS.

The U.S. District Court ruled on the lawsuit without getting to that claim, and eventually, “Izembek ended up being my favorite albatross,” said Psarianos.

Meanwhile, the proposed Pebble mine was still in play as industry pressure to mine the headwaters of Bristol Bay bumped up against the wishes of influential friends to the Trump administration, who wanted to protect the region for recreation and associated lodges. Donald Trump, Jr. went public with his opposition in 2020. News about the fight got heated and went global, as we continued diligently focusing on coupling science with legal strategy.

Remarkably, the Army Corps of Engineers denied a key permit for the proposed Pebble mine in November 2020. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency later issued Clean Water Act protections for Bristol Bay in 2023, prohibiting any mine like Pebble. A bevy of lawsuits challenging that decision followed, and Trustees intervened in all of them.

We had more great news this decade concerning 28 million acres of D1 lands across the state. They were called “D1” because of the section of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 that removed them from mining and mineral leasing. These lands scattered across the state from Bristol Bay to the Yukon-Kuskokwim, and across the interior and Arctic regions that nourish salmon, caribou, moose, and migratory birds, and are important to the cultural traditions and food security of Alaska Native families and communities.

Trustees worked with groups to comment on the Bush administration’s draft resource management plans for areas they proposed to lift those withdrawals. That administration adopted those plans, but the Obama administration didn’t act on those Bush-era recommendations. When Trump came into office, Interior moved forward with the withdrawals and issued orders to lift them. The Biden administration then paused the orders because of legal issues and undertook an environmental impact statement to study the impact of withdrawals to Tribes and lands and waters across the state. After receiving comments from Trustees, Tribes, and many organizations and people advocating for continued protections of these lands, Interior issued a final decision in August 2024 to maintain protections in place for over 50 years. Again, an enormous win.

We won, too, in the Alaska Supreme Court when it ruled in our favor to uphold the constitutional right of Alaska citizens to raise issues and vote on them. The ruling allowed an initiative updating and strengthening state law to protect fish habitat to appear on the 2018 November ballot. The measure lost in no small part because of the onslaught of extraction industry ads and influence.

Attorney Valerie Brown loved that bear suit and wore it in 2017 to stand up for the health of salmon. She argued in court for the right for citizens to raise issues and vote on them through ballot initiatives.

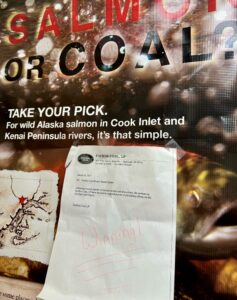

Wildlife issues were also in the mix. In January 2017, after Trump was elected for a first term, the State of Alaska and Safari Club filed separate lawsuits challenging U.S. National Park Service and Fish and Wildlife Service regulations that prohibited aggressive sport hunting methods targeting bears and wolves on national preserves and refuges in Alaska. We intervened to defend those protective rules.

The backdoor deals, new rules, and rushed analysis angled toward pre-determined decisions were the norms of that first Trump administration, when federal administrative functions were derailed and precedents dismissed.

“It was more about holding the line than making gains,” said Clark. “And that is hard.”

The legal understandings or misunderstandings made cases harder to bring and argue, and higher court rulings undercut the established interpretations of environmental laws. For lawyers and judges alike, the period brought instability.

“I feel like the legal system has changed,” said Brown. “I feel like standing has changed. Agency deference has changed. If I went back into practice, I would have to take constitutional and administrative law courses all over again. I would not have expected it to change so much so quickly.”

2020 vision

In hindsight, it’s clear that 2020 defined our work in that decade and beyond. It was a slow build during Trump’s administration to a deluge of decisions and ensuing lawsuits with enormous implications for people, animals, public lands, and climate.

In January 2020 we challenged a second land swap deal negotiated by Sec. Bernhardt to put a commercial road in Izembek Refuge. We won our first lawsuit over Trump’s first land swap deal in 2019 in U.S. District Court. A land swap would threaten subsistence resources and be a dangerous precedent for swapping lands in Alaska’s national parks, refuges, and designated wilderness areas to make way for commercial and other projects.

Months later in August, we took multiple agencies to court in four lawsuits—one challenging approval of ConocoPhillips’ massive Willow oil and gas project in the western Arctic, one challenging the Arctic Refuge leasing program, one challenging issuance of permits for the proposed Ambler road project, and another challenging a plan to open up more of the western Arctic to oil and gas leasing and industrialization.

Months later in August, we took multiple agencies to court in four lawsuits—one challenging approval of ConocoPhillips’ massive Willow oil and gas project in the western Arctic, one challenging the Arctic Refuge leasing program, one challenging issuance of permits for the proposed Ambler road project, and another challenging a plan to open up more of the western Arctic to oil and gas leasing and industrialization.

That same month, we also sued the Interior Department and National Park Service for illegally adopting a rule that would open up national preserves in Alaska to destructive hunting practices like killing brown bears over bait and killing wolves during the denning season. We had already intervened in the Safari Club lawsuit in 2017, which got split into two, one focused on national parks, the other on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge.

In 2021, we sued the Biden administration for issuing a regulation that allows oil and gas companies on the North Slope to harass Southern Beaufort Sea polar bears in the Arctic, which would likely kill cubs over the 5-year span of the rule.

Lawsuits begat lawsuits in this period of disorder and power play, while every court win meant preparing for the next legal battle, and every loss meant going in for the next fight.

The good, the bad, the messy

How did these lawsuits play out?

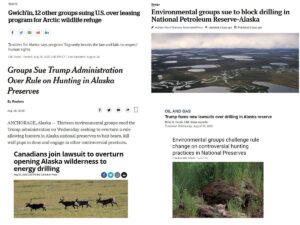

Well, we had a mighty win when a U.S. District Court judge voided flawed Trump-era approvals and permits for the ConocoPhillips’s Willow Master Development Plan in 2021. This was our first Willow lawsuit, before it became the poster child for disastrous new oil and gas drilling projects with expansive climate consequences.

Millions of people galvanized around the “stop Willow” effort in March 2023. Photo by Dawnell Smith

The Biden administration picked up where the Trump administration left off, doing a supplemental environmental impact statement to try to clean up the legal problems and then approving the project again—so we sued again in November of 2023, a time when “Stop Willow” had become a call for climate sanity across the country and world. As we go into another winter work period for ConocoPhillips, we’re still waiting for a decision in that case from the Ninth Circuit.

Our 2020 Arctic Refuge case went into pause mode when the Biden administration took office and suspended the leasing program. The waiting game centered on the Biden administration doing a supplemental review to address the serious legal problems left in the wake of the Trump administration. Although the 2017 Tax Act requires a leasing program, it cannot be one that violates laws, and defies science and the rights of the Gwich’in Nation.

Meanwhile, we intervened in two other Arctic Refuge lawsuits in 2021 and 2023—one brought by the State of Alaska and Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority challenging the Biden administration’s suspension of leases, and the other brought by AIDEA challenging the cancellation of leases. We won the challenge to the suspension of leases in federal District Court — where the court strongly agreed with us and the federal government on every single ground that it was within Interior’s authority to pause activities and address the legal errors. AIDEA appealed that decision. All three lawsuits are still pending.

This month, Interior finally released its supplemental environmental impact statement for the Arctic Refuge leasing plan, with more guardrails and protections, though not the forever protections this place demands and only Congress can give. The 2017 Tax Act requires another lease sale, and we expect another lease sale before Trump takes office for a second time.

Our Ambler litigation paused in 2021, too, while the Biden administration did another environmental review. We continued to work with clients and partners in elevating the views of local people who overwhelmingly do not support the road and in building a record that shows the impact the road would have on air and water quality, caribou migrations, and more. The draft impact statement came out at the end of last year, and we again produced thorough comments advocating for no road.

Ambler River headwaters. Photo by Ken Hill NPS

We saw a massive win on Ambler when Interior chose the “no action alternative” in summer 2024. That decision took into consideration the overwhelming feedback Interior heard from people along the proposed route and reaffirmed that it was not in the public interest or consistent with the law for Interior to approve that project. Despite that, in June, Alaska Sen. Sullivan snuck in in an amendment to an annual defense bill to force approval of the Ambler road — ignoring the input of community members and siding instead with industry. Congress is still considering that measure. We will see Ambler proponents pushing that project again in the months and years to come.

Our lawsuit challenging the Trump administration’s effort to expand oil and gas leasing in the western Arctic, or the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (a government name coined in the 20th century for a region that has sustained abundant life for millennia), also paused after the Biden administration took office. The U.S. Bureau of Land Management announced in 2022 that it would reverse the Trump-era plan to open nearly all of the Reserve to oil and gas development. In 2024, the agency also adopted new regulations focused on ensuring maximum protections for 13 million acres designated as Special Areas in the Reserve and a means for adding new protected areas.

We lost our case around polar bear harassment in U.S. District Court, so we took it to the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. We understood the math—that a significant number of polar bears would be impacted—and that the Marine Mammal Protection Act clearly prohibited that. Thankfully, the 9th Circuit Court understood the math, too, and ruled in our favor, compelling the agency to fix the legal errors in its rule. We were and are committed to protecting an already vulnerable population of polar bears grappling with the climate crisis and industrialization.

With hunting regulations, things were complicated. In 2020, we won our 2017 case defending a 2016 U.S. Fish and Wildlife rule formalizing longtime prohibition of brown bear baiting and other intense predator hunting practices on national refuges in Alaska. The State of Alaska and Safari Club appealed, so we were in the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals defending Fish and Wildlife’s rule in 2022. The Safari Club and the State of Alaska tried to get the case heard at the Supreme Court, but that Court refused to hear the case in 2023. This means no bear baiting in the Kenai Refuge, a huge win for bears and wolves, and the people who visit that refuge and care about the safety of people who go to the refuge to boat, hike, take photos, and see animals.

Meanwhile, our lawsuit around hunting in national preserves went into pause mode so the U.S. National Park Service could review and produce a new proposed rule, which the agency did in 2023. It appeared to be a step in the right direction at the end of the decade, but when that rule came out in June 2024, it prohibited bear baiting but did nothing else to protect bears and wolves. We’re still working to address hunting rules on federal lands.

Bridget Psarianos, senior staff attorney with Trustees, in a Pasadena courtroom before oral argument on Izembek in 2022. Photo by Dawnell Smith

Which brings us back to Izembek. We won our 2020 case in August 2021 in the District Court. Interior appealed during the Trump administration, and the Biden administration defended that appeal. In December 2022, we joined oral arguments in the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in Pasadena before a panel of 11 judges. Before the court could rule, Interior Secretary Haaland withdrew the land trade deal, and the Court later dismissed the case as moot.

This month, Sec. Haaland released a draft supplemental environmental impact statement that offers a disjointed argument for a land exchange to make way for a road.

Few Alaska conservation issues go away. Not quickly. But coal never got a foothold. Many mining and oil and gas projects that loomed over communities are still just proposals, not projects. Not inevitables.

In this work, you know there’s another shoe to drop, and you’re ready for it; you’re proud to do it, because that’s what it means to celebrate this place.

So here we go—into the next decade and next 50 years.

We did so much good work together the last 50 years, let’s celebrate it! Trustees turns 50 on Dec. 16 and would love for you to come join us for food, drinks, stories and a big bear hug for our collective love of Alaska the last 50 years and in the 50 years to come.