What does the Endangered Species Act do?

By Madison Grosvenor

Alaska is undergoing rapid change. Melting sea ice, thawing permafrost, and rising temperatures are transforming ecosystems at an unprecedented pace. At the same time, industrial expansion through oil and gas drilling, mining, logging, and road-building is pushing into previously remote areas.

Polar bear leaping across the sea ice. Photo by Florian Schulz.

From melting permafrost to expanding industry, Alaska’s fragile ecosystems are feeling that pressure, and so are the species that call them home.

The Endangered Species Act, passed in 1973, was the result of decades of rising environmental awareness and a push to better protect wildlife in the U.S. Its foundation was laid by earlier efforts like the Lacey Act of 1900, which cracked down on illegal wildlife trade, and the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966, which offered limited safeguards for native species.

But as the extinction crisis gained traction with the public and scientists alike, those early laws weren’t enough. Before the ESA became law, Congress held hearings where witnesses warned that species’ extinctions were rapidly accelerating—and that this “trend was something other than the process of natural selection.” Instead, human activities had, according to the 1973 House Hearings, “resulted in a dramatic rise in the number and severity of threats faced by the world’s wildlife.”

The urgency of the situation was underscored by a stark realization: half of the recorded extinctions of mammals over the past 2,000 years had occurred in just the most recent 50-year period.

Fueled by the energy of the 1960s environmental movement and the momentum from major legislation like the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, Congress passed the Endangered Species Act with strong bipartisan support. President Richard Nixon signed it into law on December 28, 1973, establishing wide-ranging protections for threatened species and their habitats and signaling a shift in how the U.S. approached environmental policy.

How does the ESA work?

The Endangered Species Act is a key federal law that protects plants and animals at risk of extinction. When a species is granted protection under the Endangered Species Act, it becomes a “listed” species. Listed species fall into two categories: endangered, which means they are in immediate danger of extinction, and threatened, which means they are likely to become endangered in the near future. When species are being evaluated for possible protection, they are considered “candidate” species.

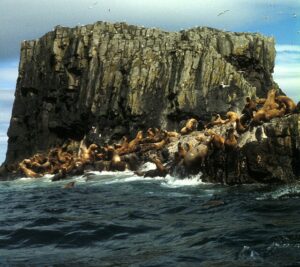

Steller sea lions are listed as endangered under the ESA. Photo courtesy of USFWS.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service are responsible for reviewing species and deciding whether they should be listed. To do this, they rely on scientific data collected by local, state, and federal researchers. They look at a variety of factors to determine if a species is in trouble. These include whether its habitat has been lost or disrupted, whether it is being overused by hunting, fishing, or research, whether it faces threats from disease or predators, whether existing laws are failing to protect it, and whether human activity is affecting its long-term survival.

This evaluation process helps ensure that species most at risk receive protection. Once listed, they may benefit from conservation efforts, habitat protection, and recovery programs required under the ESA to help bring them back from the brink.

Take, take, take

Steller’s eider pair in the Arctic. Steller’s eiders are classified as endangered under the ESA. Photo by Peter Pearsall.

Once a species is listed under the Endangered Species Act, it becomes illegal for any person, including individuals, businesses, or government agencies, to “take” that species without a permit. The term “take” includes actions such as harassing, harming, pursuing, hunting, shooting, wounding, killing, trapping, capturing, or collecting a listed species. It also covers indirect impacts that result from damaging or destroying a species’ habitat.

Importantly, “harm” under the Act doesn’t just mean direct physical injury. It includes significant habitat modifications or degradation that actually kill or injure wildlife by disrupting essential behaviors like breeding, feeding, migrating, or sheltering.

These protections are particularly important in Alaska, where large, relatively undisturbed ecosystems support a wide variety of unique and sensitive species. The Cook Inlet beluga whale, Steller sea lion, and spectacled eider are just a few examples of Alaskan wildlife that rely on intact habitats for survival. As pressures from resource extraction and climate change grow, the Act plays a crucial role in protecting the species that help define Alaska’s natural heritage.

Success stories of Alaska

Trustees for Alaska has long used the Endangered Species Act as a critical tool to protect Alaska’s most vulnerable wildlife, particularly in the face of rapid environmental change and industrial expansion. Alaska is home to 13 endangered species and 8 threatened species, with at least 6 species under consideration for protections. One of these is the iconic Cook Inlet beluga.

Cook Inlet beluga calf surfaces in the Turnagain Arm. Photo by Paul Wade, NOAA.

The Endangered Species Act allows “any interested person” as well as organizations to petition the federal government to list a species as threatened or endangered, triggering a legal review of the species’ status and the threats it faces. In fact, the vast majority of species listings throughout the history of the Act have occurred as a result of citizen petitions!

Once a petition is accepted, it can lead to critical protections for the species and its habitat under federal law.

Back in 1999, Trustees and a coalition of groups, along with a former whale hunter, petitioned the federal government to list the Cook Inlet beluga as endangered under the Endangered Species Act, citing a staggering 50% population decline in just four years. The petition also requested emergency protections to halt unsustainable hunting, habitat loss, and pollution while a full listing decision was made.

The Act served as a powerful tool used to address the full range of threats facing the belugas, from unregulated hunting to oil and gas development in their shrinking habitat. Trustees argued that without immediate and enforceable protections under the Act, the species would continue its rapid slide toward extinction.

After 10 years of advocacy and petitioning, Trustees and our clients got Cook Inlet belugas listed.

Critical Habitat

When a species is officially declared endangered or threatened, federal protections don’t stop at the animal or plant itself, they extend to the land it calls home. Under the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is generally required to designate “critical habitat” at the same time a species is listed.

Beaufort Sea ice. Approximately 187,000 square miles of Alaska’s Arctic coastline — including barrier islands, denning areas, and offshore sea‑ice in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas— was designated as critical habitat for polar bears. Photo by Florian Schulz.

This critical habitat can include not only areas the species currently occupies but also places it doesn’t yet inhabit, if those areas are deemed vital for long-term survival. For currently occupied habitat, the ESA defines critical zones as those containing specific physical or biological features essential to the species’ recovery, and which may need special protection or management.

Unoccupied areas can also qualify, though only if the agency determines they’re essential for the species’ conservation. And “conservation” here means more than just survival: it refers to all steps needed to recover the species to a point where it no longer needs Endangered Species Act protection.

Ultimately, courts have emphasized that the goal of critical habitat designation is clear: map out the landscapes that must be preserved or restored to give threatened wildlife a real shot at recovery and eventual delisting.

The Act in action

In March 2023 Trustees filed a lawsuit charging the Interior Department and multiple agencies with illegally approving the controversial Willow Project, ConocoPhillips’ massive oil drilling extraction operation on Alaska’s North Slope.

Willow would expand ConocoPhillips’ extensive oil and gas extraction operation in the Arctic and become a hub for future industrialization, spewing out toxic emissions and greenhouse gas pollution. It would have dramatic impacts on local communities whose culture centers on caribou and subsistence practices.

Polar bear on ice floe in the Beaufort Sea. NOAA.

It would also have significant impacts on the Southern Beaufort Sea polar bears, a species already listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act because of climate impacts reducing populations to near extinction levels. Polar bears depend on the North Slope region for essential life functions, including hunting, denning, and survival. This population faces mounting pressures from the climate crisis as well as impacts from oil and gas activities in its critical habitat, putting it at heightened risk of endangerment.

In late July of 2023, we filed our first brief in the Willow lawsuit, calling out agencies for unlawfully approving the project.

The Endangered Species Act is one of the nation’s strongest environmental laws, designed to prevent federal actions from pushing vulnerable wildlife closer to extinction. To meet that goal, agencies like the Bureau of Land Management must consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to ensure their projects won’t jeopardize endangered species or destroy critical habitat. But in approving the massive Willow oil project in Alaska, both agencies appear to have broken those rules.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service failed to consider how Willow’s greenhouse gas emissions—millions of tons over decades—would accelerate climate change and worsen sea ice loss for polar bears, a species listed under the Act precisely because of its shrinking Arctic habitat.

This omission ignored the Endangered Species Act’s requirement to use the best available science and consider all foreseeable effects of an action, not just the immediate ones. Despite this, we lost this argument in District Court. This case highlighted how the Endangered Species Act’s protections can be undermined when agencies sidestep scientific evidence or narrow the law’s definitions, especially in the face of climate-driven threats to Arctic species like the polar bear.

Imperiled futures

In Alaska, the future of the Endangered Species Act faces mounting threats, not only from climate change but from shifting political and regulatory priorities that weaken its enforcement.

Federal rollbacks, pressure from the fossil fuel industry, and legal interpretations that narrow the scope of what constitutes “harm” or “critical habitat” could chip away at the Act’s protective power.

Polar bear and two cubs walking along ice floe on Beaufort Sea. Photo courtesy of NOAA.

For species like the polar bear, whose survival hinges on confronting the climate crisis head-on, this erosion of safeguards can be devastating. With Alaska’s ecosystems undergoing rapid transformation, from thawing permafrost to shrinking sea ice, a weakened Act could mean fewer tools to address the accelerating risks.

Yet one of the Endangered Species Act’s greatest strengths lies in its clarity: protect means protect. It definitively tells agencies what they can and cannot do to protect listed species and their habitats, setting enforceable limits backed by science and law. This legal precision gives the Act real teeth and genuine power to stop or reshape projects that threaten vulnerable wildlife and their critical habitats. After all, it is the law.

Conservation groups, Alaska Native communities, and we at Trustees continue to fight for the law’s full application.

In places like Alaska, where climate impacts arrive faster and hit harder, the Endangered Species Act remains a critical tool, if it is allowed to function as it was intended.

This is the fourth in our “laws under fire” series. You can find previous articles below: