How do you make a clean city?

What makes Tracy Lohman thankful every day? Knowing that she can count on clean water and air, and that her children can count on it, too. Now she works to fight for clean water and air for everyone. Here’s her story about why she loves her work as development director for Trustees for Alaska—and why she knows this work can succeed. Part of her passion is knowing how to make a clean city.

What are they making, pollution?

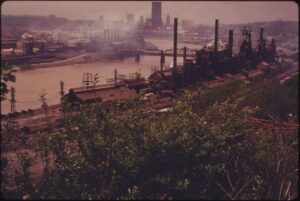

Growing up in the outskirts of Pittsburgh, once referred to as “hell with the lid off,” it was a common sight to see smoke billowing from the stacks of the steel mills. In 1970, on our way through the industrial district to Kennywood Park, Pittsburgh’s best amusement park, I asked my parents what they were making as we drove past.

“Pollution?” I wondered.

I was too young to realize that the steel industry was the economic backbone of Pittsburgh, but I knew what I saw looked ugly and smelled worse. No one in my family worked at a steel mill. I didn’t know much about them. I imagined birds flying through the black soot and fish swimming in the Monongahela River below. How would they survive?

Weekends at Pymatuning Lake

Every Friday after dad got home from work, we would load the pickup with our camping gear and head to the lake. For dinner, it was PBJs on the road. We’d pitch our tent at the KOA campground, always in the dark and often in the rain. On Saturdays, we would spend eight hours on the water. The goal was to catch the biggest walleye in the lake. We never did catch the biggest walleye, but we did catch a lot of fish.

Listen to your parents

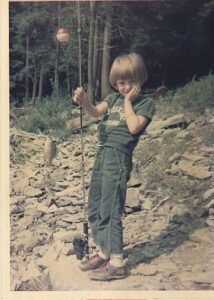

“Go play outside and don’t come back until dinner,” the grownups said, and so we did. Getting outside was not only encouraged, but it was an essential family value.

From an early age, my parents introduced me to the wonders of the natural world. When we weren’t fishing or camping, we were hiking, climbing rock ridges, or paddling down a river. We got around on bikes.

Smoggy air, infected water

It wasn’t until college that I started to fully appreciate the environment and my connection to it. In 1984, the water of McKeesport, the city where I was born, was infected with giardia due to an aging water system. A community already disenfranchised and suffering economically from the collapse of the steel industry now lacked access to clean water. I believed then, and believe now, that having clean water and are basic rights. How could 45,000 people not have access to clean water?

Location, location, location

Lines drawn on a map long before I came along created the devastating and long-lasting consequences that polluted the water and air where I grew up.

Back in 1933, in the middle of the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal included the founding of the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) to help stabilize a depreciated real estate market. The organization created something called “redlining,” a process that categorized risk levels of lending in urban neighborhoods.

Although the HOLC map did not specify the predominant race in various neighborhoods, all lenders knew that red areas were overwhelmingly African-American. Redlining prevented African-American families from obtaining mortgages. The discriminatory practice led to further impoverishment for those families, and a disproportionate level of pollution in those poor neighborhoods.

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 later banned the practice, but the inequity and discrimination of redlining continues to impact residents of those “redlined” neighborhoods now.

Making a place clean means fighting to keep it clean

After the steel industry closed in 1983, Pittsburgh transformed itself. The city successfully shifted from factories to high technology, health care, finance and education. Pittsburgh[1] has earned praise as “the poster child for managing industrial transition” and is now home to six Fortune 500 Companies. Its mayor co-wrote an article with the mayor of Paris, France, in asserting their own climate deal and commitment to fight climate change and “build a cleaner, healthier, more prosperous world for Parisians, Pittsburghers and everyone else on the planet.”

The air, too. has gotten easier to breathe. Yet there is still work to do. Earlier this year, the city told 100,000 Pittsburgh residents to boil their tap water due to high levels of lead, again the result of ever-aging pipes below the city. The Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority warned its residents that water could again be contaminated by giardia. Interestingly, many of the neighborhoods with contaminated water mirror the “redlining” map of yester-year.

A long way from Pittsburgh

I made Alaska my home in 1990. It’s pretty far from Pittsburgh. It’s true, too, that the air and water are cleaner here. I feel fortunate to breathe Alaska’s fresh, clean air every day and fish for wild salmon in its fresh, clean waters.

Why shouldn’t all people, regardless of where they live and their socio-economic status, have access to clean air, clean water and healthy food? For me, conservation is a social justice issue. I wake up every day and get to work with the best and the brightest environmental lawyers.

We know that together we can help keep water, air and food clean for our Alaska communities and all the people around the world who like knowing that they can visit and experience pristine places.

I will not stop doing this work until there is equal access to clean air, clean water, and healthy food for all people from Anchorage to Pittsburgh and around the globe – including my two boys.

My thoughts on pollution haven’t changed much since I was 5—it’s dirty, it stinks and I want to help reduce it—but many, many other things have. Like, for instance, how I’m now the one telling my kids, “Go play outside and come back when it’s time to make dinner.”