Drinks with lawyers—Rachel makes a case for shiny red shoes

By Dawnell Smith

Rachel’s family knew she would be a lawyer before she did.

Her grandfather used to tell her that long before she knew a thing about the legal field, but she didn’t buy it—maybe because she didn’t like other people telling her what to do, or maybe because she was the family member who would argue with him about anything, or because she was just a kid with an imagination as broad and expansive as the future.

Whatever the case, no one doubted her penchant for advocacy.

Take the story of the shiny red shoes. When she was 4 years old, Rachel wanted to go to preschool wearing shoes that her mother considered inappropriate, too large, and too slippery. “She mounted a rather sophisticated and ultimately successful argument—a series of unrelated (I thought!) questions that resulted in my begrudging agreement,” said Jill Briggs.

Or as Rachel put it, “Apparently I asked a bunch of questions about whether she liked this color or that color better, whether she liked shiny things or not, and so on, until I concluded that the sparkly red shoes were the only possible choice.”

You might say Rachel understood early in her life that an argument required questions, evidence, and clarity, and that you needed a rock-solid argument to influence people who made the decisions for and about you.

From the island life to law school

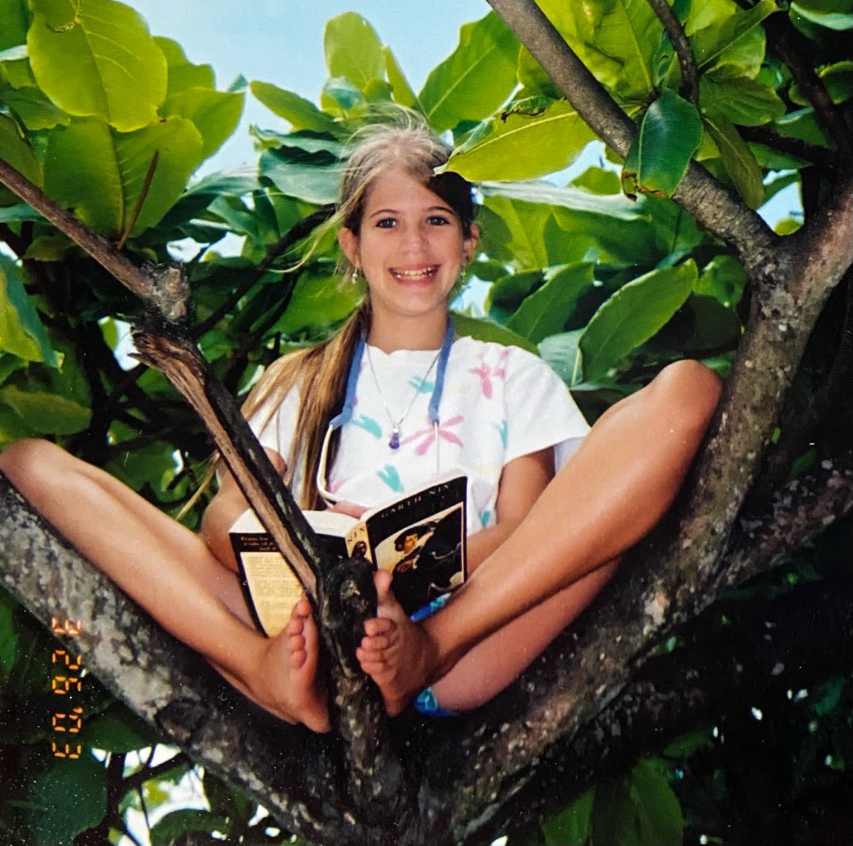

Rachel grew up in Hawai`i where her moms, who nudged her outdoors, often with books in hands, raised her to be an activist.

She always showed a willingness to stand up for her beliefs and the confidence to express them, said Jill. “From early on Rachel frequently expressed awareness of social justice challenges along with a strong desire and sense of responsibility to care for and protect the natural environment.”

So, after graduating from secondary school, Rachel headed to College of the Atlantic in Maine, another coastal state, where she studied ecology and the environment. She found the environmental law classes rewarding, but she didn’t jump into law school right after graduating. A professor told her that law school changes how you think, she said, and she wanted to make sure that’s what she wanted.

Instead, she did advocacy work as an organizer in Washington, D.C. for the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance for a few years. But her tendency toward introversion and love of research, writing, and book work pulled her again to the law.

“I liked the idea that I could be an activist and a rule follower at the same time,” she said. “And I guess I realized, too, that I did want to change how I think.”

What, you’re offering me my dream job?

Now as a young lawyer, Rachel does just that. She likes knowing where the guard rails are thinking through whether they makes sense. She presents her thoughts and views in a precise way, measured in tone, powerful, and on point. She also has a remarkable way of being both gentle and forceful at once—kind in her ferocity, steadfast through her vulnerability.

“In my experience, there are many smart people who can construct logical arguments, but few have Rachel’s way of using logic to support empathy,” said her partner Bradley Pizzimenti. “That combination makes her a lawyer with the heart of an activist or an activist with the tools of a lawyer — in other words, an oralist to be reckoned with.”

Her work with Trustees centers on public lands and wildlife protection, areas that have profound meaning to her and her values around healthy systems of life for humans and more-than-humans alike.

The benefit of this kind of work is also the cost, she said. “We care so much and it’s hard to lose, to think you were in a position where you could have done something differently and maybe gotten a different result.”

There has been good news in her area of litigation the last few years. Prohibitions on bear baiting in Kenai National Wildlife Refuge and in national preserves have been upheld in court and supported by federal agencies. The Bristol Bay region is protected from projects like the proposed Pebble mine for now.

The issues never go away, of course, though people do. Several of Rachel’s early trusted mentors have moved on from legal work for now, and she misses those relationships. Former legal director Brian Litmans and senior staff attorney Katie Strong built a foundation for Trustees’ wildlife and public lands work over a dozen or more years, and helped Rachel gain a depth of knowledge and understanding to take over those cases.

Though not alone by any means, Rachel feels their loss sometimes. Not to mention that her role from legal fellow to Trustees litigator happened quickly.

After finishing law school at Lewis and Clark, she took a law clerk position with the Alaska Supreme Court and then joined Trustees as a legal fellow in 2019. Several months later, in the midst of COVID as everyone learned to work entirely at home, she transitioned into a staff attorney position.

It felt overwhelming and surreal, she said, like, “What? You’re offering me my dream job? Now?”

The law is not a rule book

The thing people should know about the law is that it moves slowly, she said, and that in environmental law, the cases are fact-heavy and involve laws that are applied in different ways.

“The law is not a rule book,” she said. “The law is always relative, always by analogy, always interpreted. It is not rote.”

Environmental laws, like civil rights laws, were written in the 1960s and 1970s, which makes them fairly new and dynamic—things are still getting worked out, they are subject to push-pull, and there is constant change.

This makes the work exciting, challenging, emotionally draining, intellectually rewarding, life-consuming and much more, particularly in a landscape where there’s so much political division and so many efforts to undermine laws that protect clean water, animals like bears and wolves, and public lands that nourish abundant life precisely because they have not been industrialized or carved up by commercial projects.

The legal effort to uphold these laws and to make sure they’re followed isn’t getting any easier. Staying effective as an environmental attorney means staying healthy in every way, sustaining trust and purpose, and connecting with community.

When things go poorly, Rachel might shed some tears, commiserate with others, make space for emotions, and then look for and find the lessons she can carry forward. When there’s success in court, she might talk with her colleagues about “how right we were,” and/or connect with friends over drinks, and/or simply celebrate by sleeping.

Larger than life truths

Rachel can’t say how long she’ll stay in Alaska, though after five years here she finds many similarities between the island life she grew up with and where she lives now—the misconceptions about the place and whether it’s part of the United States, the superficial myths and bigger than life truths, the way the landscape shapes the people.

There were surprises, too. “Something I didn’t understand until I got here is how large and diverse Alaska is in terms of the types of landscapes, people, and cultures,” she said.

Her role with Trustees allows her to advocate for all of it, whether finding paths for protecting Cook Inlet beluga whales and Kenai brown bears, or keeping mining corporations from polluting waterways important to local people, salmon runs, and the complex interrelations between animals and plants and human communities.

Truth is, when it’s hard to step back and see all the pieces of a strategy working together to protect an animal, a place, or the planet, nothing brings clarity like seeing a bear feeding on the Kenai river, and holding that moment and memory of an old and essential relationship, and knowing you did something to respect and honor it.

That’s the pair of shiny red shoes Rachel argues for—again, and again, and again.

This is the third in a series of profiles based on interviews with Trustees’ attorneys over drinks, this time over sours and ales at Turnagain Brewing in Anchorage.

More in the drinks with lawyers series: