Permitting process severely underestimates mining spills in Alaska

By Dawnell Smith

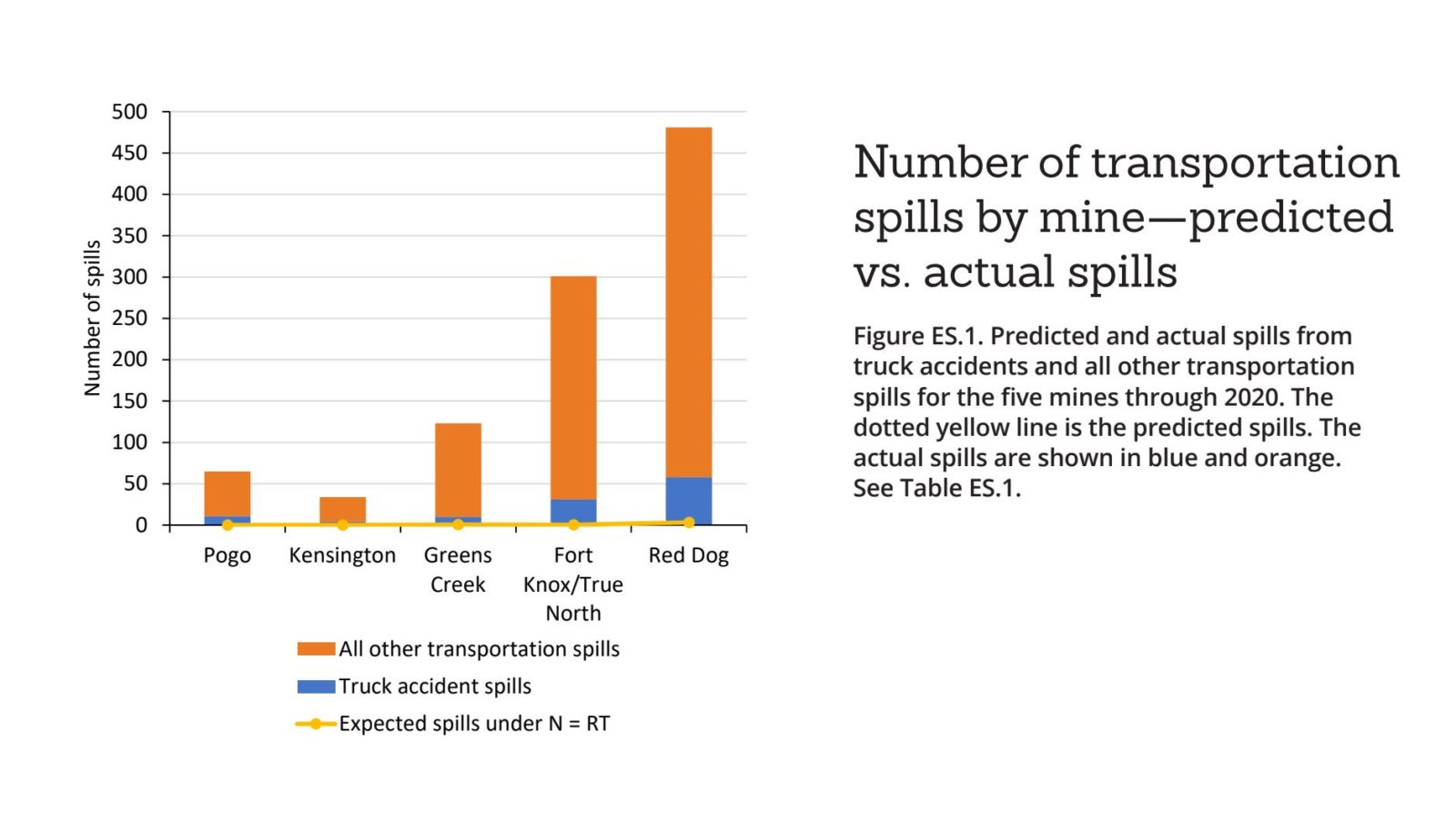

A report released this month shows that the number of documented spills between 1995 and 2020 at the five major operational hardrock mines in Alaska far exceeded those estimated in permit applications and environmental reports.

It concluded, among other things, that the environmental review process did not regularly include a quantitative spill analysis or look at the cumulative risk of all types of spills of all kinds of hazardous materials.

A huge gap in knowledge

Alex Johnson, senior program manager for the National Parks Conservation Association, said the report really stood out to him as spotlighting the huge lack of information about the real impacts of mining in Alaska. The NPCA is one of five groups that requested and funded the report and has for years tracked projects like the Ambler transportation corridor proposal.

He said communities, tribes and groups like NPCA have flagged the lack of information from the beginning, but even he was surprised at how inaccurate the estimates and poorly equipped the prediction models really were.

The models used in permit applications and environmental reports for the five major mines in Alaska only offered estimates of certain types of spills, like truck accidents and slurry pipeline spills. None of these mines—the only major mines in the state–addressed spills caused by equipment failure, yet equipment failure caused 40 percent of the over 8,000 documented spills from those mines.

“The scale of the error, the scale of how much we didn’t know, even after decades of these mines operating in Alaska, was shocking to me,” said Johnson.

Lisa Baraff, the program director and climate change & energy program manager for the Northern Alaska Environmental Center, said the reports should prompt significant change in how agencies analyze permit proposals.

“We hear industry spokespeople and their political allies talk about the stringent permitting requirements and regulations in the United States, and wow, this report puts huge holes in that assumption,” she said. “The fact is that agencies are permitting projects without having vital information and the people most impacted by these mines, who are already systematically excluded from the decision-making process, are the ones living with the consequences.”

Garbage in, garbage out

The report shows that mining proposals were approved despite a dearth of data on how they really impact land, water, air, animals, and people.

The good news is that Alaska has a database that documents spills.

“That no one has gone in there to see what was being spilled, how much, how often it was being spilled until now is stunning,” said Johnson. “But now we can say, this is exactly how much was spilled and this is why and how, and that makes it a more complete picture. Now it’s possible to make much more informed decisions. That is, if the agencies are willing to do the work of looking at the facts before issuing permits.”

The report was sent to federal and state land managers at agencies like the U.S. National Park Service and Bureau of Land Management, among others, with a letter calling on agencies to revisit how they review permit applications and their environmental reviews.

The report’s author Dr. Susan Lubetkin wants the report to improve the permitting process. “My hope is that I can inspire the state of Alaska and others to increase their demands for scientific rigor by pointing out one area where previous permitting documents have been lacking and their predicted impacts have been wrong,” she said in a statement overviewing the report’s findings.

The report was prepared for and funded by the Brooks Range Council, Earthworks, National Parks Conservation Association, Norton Bay Intertribal Watershed Council, and Tanana Chiefs Conference. It looked at spill data for the Pogo, Kensington, Greens, Fort Knox/True North, and Red Dog mines. Download the report here.

NPCA and the Northern Center are plaintiffs in a 2020 lawsuit charging the Interior Department, Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service and Army Corps of Engineers with breaking multiple federal laws when permitting the Ambler road proposal. That case is still being litigated.