The second decade—dialed up to 11

By Dawnell Smith

If you sum up the 1980s in a few words, you can choose your own adventure—the mix tape, acid-washed jeans, Nintendo, the “war on drugs,” yuppie culture, the Tiananmen Square protests, cable news and MTV, and of course Wall Street excess. With the 80s came the last decade of the Cold War and the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, the rise of the computer age and the fall of the Berlin wall.

Commercial boat near Alyeska oil terminal protesting foreign-flagged tankers, 1988.

The societal volume nob on greed was cranked up to 11 in the 80s. (Yes, this is a “Spinal Tap” reference.)

For Trustees for Alaska, the 80s meant its workload dialed up to 11, too. With Alaska thoroughly framed as a “resource colony” by then, a slew of industry exploration and extraction proposals endangered landscapes still threatened by mining and drilling to this day—places like the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Bristol Bay, the Brooks Range, the Chukchi Sea, and the western Arctic.

The Exxon Valdez oil spill catastrophe elevated the grave and deadly consequences of oil industry irresponsibility and policies that fail to provide environmental protection, while that same industry proved that it would do anything to get its way, whatever the consequences suffered by others. The Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. even hired a spy agency to rummage through Trustees’ trash to find dirt on a whistleblower!

There’s a reason the 80s provide the contextual backdrop for “Stranger Things”— and for why a small Alaska law firm representing Alaska interests took on powerful forces despite the odds.

The mouth that roared

Trustees built the groundwork for stronger relationships with local communities and organizations in the 80s, noted Eric Smith, the executive director of Trustees from 1982 to 1986.

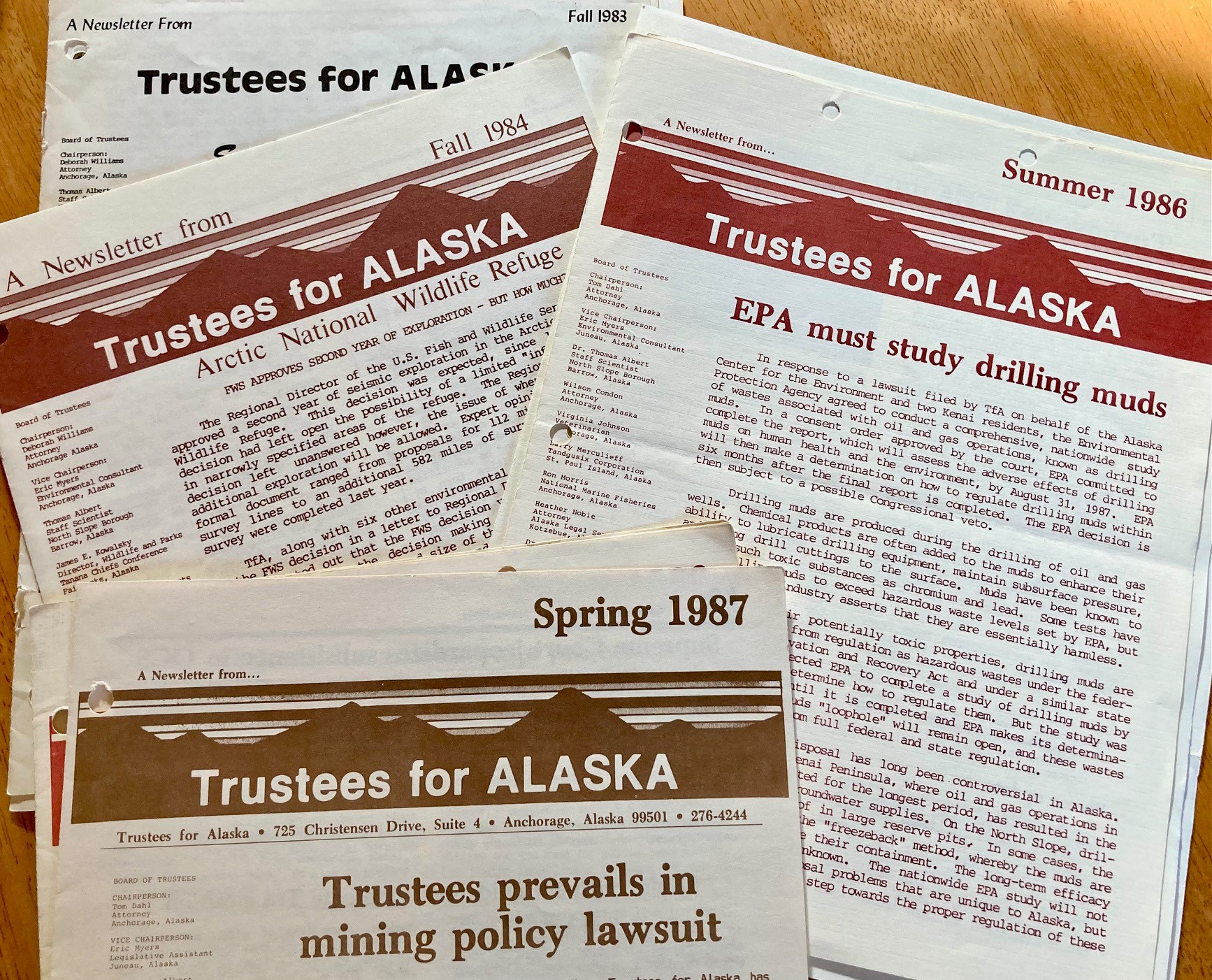

Second decade newsletters. Photo by Dawnell Smith

“In terms of outreach, it was a sea change for us,” he said. “When I got here, environmentalists were really hated up here, and we knew we had to build coalitions.”

These coalitions included villages, local governments, citizen groups, environmental groups, fishing organizations, and even the North Slope Borough. Everyone understood the importance of working within larger efforts where unity would enhance the understanding of issues while building power. These collaborations in turn allowed Trustees to play its specific and vital role in giving legal voice to the concerns of those most impacted by industry projects.

In one big case that reaffirmed the concept of taxpayer standing in Alaska, Trustees argued that the Alaska Statehood Act required the State of Alaska to collect royalties from the land it leased for mining, said Smith. Trustees represented Native Alaska communities, fishing groups, and environmental groups. The court agreed with Trustees.

Smith fondly remembers how the court noted that the appellants “are well represented by competent council who have forcefully presented their position.”

Deborah Williams, the board chair around the same time as Smith, said Trustees “was a really small scrappy organization and we did extraordinary things with a small budget and enthusiastic board. We were very mindful of limited resources, so we took care trying to prioritize where we put those resources.”

Being strategic mattered in profound ways in the early 80s “when a lot of environmental law was being made for the first time,” she said, “so it was very important to set good precedents and make sure laws were quickly and appropriately applied.”

St. Matthew Island, USFWS

Another major case involved a land exchange between three Native corporations and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Refuge to allow ARCO Alaska to establish an oil and gas base on St. Matthew Island in the National Maritime National Wildlife Refuge. The base would include an airport, roads, tanker terminals, facilities for a permanent crew, and jet and helicopter landings and take-offs.

ARCO had eyed St. Matthew for some time and approached Fish and Wildlife for permission to build the support facility, but the agency denied the request because of the area’s protected designation. Fish and Wildlife instead suggested that ARCO use the land exchange authority in the Alaska National Interest Land Conservation Act to accomplish its goals and consummated a land exchange in 1983.

Trustees went to court challenging that exchange, charging the agency with violating both ANILCA and the Endangered Species Act. Trustees won that case.

“If that exchange had gone forward, an extraordinary amount of damage would have been done via that exchange provision,” said Willams. “That case put an end to that dangerous possibility. Trustees has always been in a David v Goliath story, and it was so much a David in this case. Trustees really was the mouth that roared.”

Persistence and relationships matter

Newsletters capture the array of environmental concerns. Photo by Dawnell Smith

Trustees’ put great effort into addressing placer mining’s impact on water quality and local communities as well. Chemicals like arsenic and mercury were of deep concern because of their impact on drinking water, fish, the animals who ate fish, and local people who fished and relied on rivers and streams for their way of life. Trustees fought to put limits on the discharge and treatment of pollutants and to ensure that the concerns and needs of local people were heard and addressed.

Bob Adler, who joined Trustees as an attorney in 1984 and served as executive director from 1986 to 1987, said other key cases centered on oil and gas threats to the Arctic Refuge, state lands and the outer continental shelf, as well as massive dam proposals on the Susitna River, and hard rock mining policy.

Relationships with Alaska Native communities expanded as oil and mining pressures near those communities grew, he said.

Trustees represented the villages of False Pass and Quinhagak as well as the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission in a lawsuit challenging an oil and gas lease sale in Bristol Bay. A U.S. District Court judge ruled in Trustees’ favor in 1986, though an appeals court gave the Interior Department the okay to do the lease sale two years later. The fight to protect Bristol Bay from oil and gas drilling and mining has continued to this day.

Corporate and political pressure to drill on the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge also ramped up. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service approved a second year of seismic study in 1984, prompting Trustees to join six other groups telling the agency that its decision violated the public’s right to participate in the decision-making process and that the agency’s approval of a second year of seismic work allowed more destructive exploration methods.

Some projects never die, said Adler. “It’s much harder to prevent a bad thing from happening permanently because project proponents can always come back and try again.”

A devastating spill

The tanker Exxon Valdez running aground, 1989, NOAA

The Exxon Valdez oil spill dominated the news in 1989 and for years afterward. You can still find oil by digging shallow holes on some beaches in Prince William Sound, and many animals never recovered, with complex impacts on the entire system of life. Herring never recovered and the commercial herring fisheries have been closed for decades. A pod of locally distinct killer whales never recovered, nor did populations of pigeon guillemots, who nested on islands that took a direct hit during the spill.

The long-term impact of the spill is now intermingled with climate impacts on ocean systems and life in a climate crisis that Exxon knew about then, but hid from the world.

Right after the Exxon Valdez spill, Trustees sent a lawyer to Valdez to look into wh

at the needs were in terms of legal services, said Randall Weiner, the executive director from 1982 to 1992. Trustees ultimately decided that private tort cases were “better equipped to commence a long, drawn-out fight with Exxon than Trustees,” he said.

Front page Anchorage Times Sept. 21, 1991

In a way, the spill put a line in the sand for Alaska, at least for a time. It told the story of what goes wrong—how an industrial “accident” or “mishap” can decimate the food and livelihoods of Alaskans for generations. Those lessons stay with Alaskans today and show up in efforts to stop potentially devastating “accidents” in the future from projects like the proposed Pebble mine.

Unrelated except in terms of timing and the connection to transporting oil, Trustees got another taste of how far industry would go to do what it wants and silence opposition. The Alyeska Pipeline Service Company hired the security firm Wackenhut to drudge up dirt on opponents. One of their tactics included rifling through Trustees’ trash “looking for evidence that a whistleblower had shared confidential materials with Trustees,” said Weiner.

The U.S. House of Representatives hauled Wackenhut executives to the halls of Congress to defend their actions, and the firm later disbanded the surveillance arm of their company.

This wouldn’t be the last time someone tried crossed the line when trying to get under Trustees’ skin. (Stay tuned for our review on the third decade next month!)

What comes around comes around again

Trustees’ legal work led to several successful lawsuits in 1990 and 1993 that compelled a pre-lease analysis of the risks associated with transporting oil and a review of archeological and seismic impacts under the state’s coastal zone management program, said Weiner, now in private practice in Colorado.

“These Alaska Supreme Court decisions prevented oil and gas lease sales in Camden Bay and Demarcation Point in Alaska state waters off the Arctic Refuge coast, and have prevented oil activity in these waters for over thirty years,” he said. “Had the proposed lease sales occurred, there would have been intense pressure to allow more oil sales and drilling in and around the Arctic Refuge.”

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Photo by Lisa Hupp, USFWS.

Clearly Trustees stayed busy and on point. The typed and photocopied Trustees newsletters from the time—now kept in a binder at the office and digitally on our server—capture the scope of Trustees’ work.

A 1983 newsletter with a page 1 article titled “St. George Oil and Gas Lease Sale Enjoined” includes a story explaining why sending mining discharge into settling ponds fails to address the danger placer mining poses to people and animals.

Placer mining involves using water to separate gold from gravel, stirring up heavy metals like arsenic and mercury, which are toxic to animals and people. Over 600 placer miners were operating in the state in 1983, according to the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation at the time. The newsletter goes on to explain the threat.

“Mining discharges make the receiving waters very turbid. Turbidity, or muddiness, reduces the suitability of water for drinking, for domestic use, and for fish habitat. The presence of silt blocks sunlight and hinders growth of aquatic plants, an important food source for other aquatic life. Sedimentation from placer debris smothers eggs and fish fry and fills interstitial areas in gravel which are necessary for the oxygenation of water. Opaque water prevents sight-feeding fish from feeding—and from being caught by fishermen. The effects of turbidity can be experienced far downstream from their sources. On the Chatanika River near Fairbanks, turbidity from a placer mine ran downstream for over 100 miles…”

Aerial view of the Chuitna River.

Ten years later, a 1992 newsletter with the front-page headline, “Supreme Court Halts Diamond-Chuitna Coal Mine” includes a call to action on page 4 asking that readers send comments to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency opposing its proposal to exempt Alaska from complying with the environmental regulations for wetlands established for the entire country.

“Put simply,” says the piece, “the proposal fails to reflect the substantial values that Alaska’s wetlands provide; and it is an unnecessary response to complaints by oil and mining companies and other developers in Alaska.”

The fight to stop the Chuitna coal mine went on for decades, and the effort to protect wetlands continues to this day. What comes around keeps coming around, like all those 80s songs blaring from the oldie’s station and every next generation’s devices.

The Walkman was replaced by Bluetooth streaming. The music goes on, and so does Trustees.

Read all our 50th stories:

- Founders Peg and Rod talk about the need, the now, the future

- The first decade

- It’s our 50th. Come party with us with live music, travel, a fish-fry and more!