Trustees’ 50th year series: The first decade

By Dawnell Smith

Trustees for Alaska began as an idea and a means to fill a need. Its early architects knew that folks who cared about the environment and wanted to protect land and water, animals and communities from pollution, spills, destructive fishing and hunting practices, and an array of industrial hazards needed legal representation. Outside attorneys were doing some work, but the people who organized to create Trustees wanted an Alaska environmental law firm focused on Alaska issues.

From a newspaper story about Peg Tileston, 1976

Co-founders Peg Tileston and Rod Cameron made Trustees official on December 16, 1974. By then, work had already begun on the trans-Alaska pipeline, and corporate players and politicians saw Alaska as a cash cow. “Progress” was on many people’s minds and that often meant exploiting places and sacrificing communities and wildlife along the way.

The board consisted of three people in the beginning, the two co-founders and Robert Weeden, a professor at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks and active in the Alaska Conservation Society. The first goals included growing support and organizational structure, building coalitions, and supporting Alaskans in being heard and empowered.

From the beginning, Trustees advocated for the voices of those drowned out by industry and their narrative of Alaska as a motherlode for extractors, never mind the harm done to others and the planet. Here we are 50 years later, working to protect many of the same places alongside many of the same groups and communities.

The “little Alaska law firm that could” made a name for itself back then, and still does today, because of the people who carry it, support it, and work alongside it meet the challenges together.

More brazen than the mafia

Trustees’ early work involved plenty of lawsuits around pulp, gold placer mining, and oil leasing, along with coalition-building and influencing government decisions by submitting comments and guiding clients. But it also strayed from environmental law to help ensure marginalized voices would be heard.

An early and important effort went into bringing fairness to radio and TV broadcasting. Back then, the Federal Communications Commission had a Fairness Doctrine that required radio and TV broadcasters to air differing points of view on “controversial issues of public importance”; the agency viewed broadcasters as having a public interest role, and saw the danger of letting big broadcasters set biased public agendas.

First half of Page 2 of the list of demands Alaskans for Better Media has for broadcasters. The Anchorage Times published two full pages of the demands in its Dec. 30 issue, 1977. Courtesy the Atwood Foundation archives.

In Alaska, though, some broadcasters presented only anti-environmental views and gave short shrift to covering other issues. Trustees joined a diverse coalition called Alaskans for Better Media that included groups like the Alaska Black Caucus, the Alaska Public Interest Research Group, the Alaska Women’s Resource Center, and Alaska Native and conservation groups. Alaskans for Better Media sought more fairness in broadcasting, more hiring of Black people, Alaska Native people, and women, and other improvements in meeting the public interest obligations of broadcasters under federal law.

One radio DJ really ripped into environmentalists, and Trustees got dragged in the mud too. Rob Mintz—an attorney starting in 1976 and later executive director for Trustees for Alaska until 1981—said Alaskans for Better Media notified the broadcasters that the coalition would challenge their broadcast licenses if they didn’t agree to some changes.

It was a messy time, though, with heated exchanges and bad blood. Mintz remembers the Anchorage Times running scathing editorials that called Alaskans for Better Media “more brazen than the mafia” and with headlines like “Enemies of Freedom.” When negotiating the settlements, one station manager told Mintz that if the group challenged its license renewal, they’d be enemies for life.

Letters to The Editor from 1977 showing how some Alaskans were upset about the efforts of Alaskans for Better Media to require fairness in broadcasting. Courtesy of the Atwood Foundation archives.

Eventually, said Mintz, “We proposed an agreement with their commitments to a community advisory board, commitments to improving fairness, and we entered into a settlement agreement with two of the broadcasters.”

Many Alaskans didn’t know about the fairness requirement for broadcasters and viewed Alaskans for Better Media as sticking its nose into private companies’ business, but in the end, public service announcements were made and broadcast to bring in other points of view, and more people were represented in the media. There were lessons learned and results that made a difference.

Stopping the privatization of Alaska

One of the early and profoundly impactful lawsuits of the first decade challenged the Alaska Homestead Act, which would have privatized huge amounts of land in Alaska. The homestead initiative, which passed and became law, would have required the State to distribute a massive amount of public lands to individual citizens as private property. Trustees challenged the initiative.

The second paragraph of a 1978 Washinton Post article about the case said, “The initiative would carve up to 30 million acres of state land – an area the size of New York state – into 40-acre parcels to be given away to Alaskans who have lived in the state three years or longer.”

Later, the story noted, “One major question is whether the residency requirement is constitutional. Free Alaska land could become available to all Americans if the court striked that requirement while upholding the rest of the initiative.”

Trustees won the case in the Alaska Supreme Court.

“The areas where we now fish, hunt, and hike would have been surrounded by ‘No Trespassing’ signs,” said Wilson Rice, the executive director from 1978 to 1981. “That very high-profile case–the Supreme Court argument was televised live–was Trustees’ first significant litigation and our way of letting everyone know that there was a new kid on the block.”

Trustees for Alaska v. James Watt

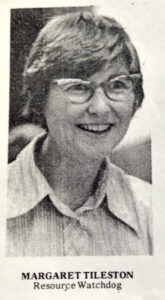

James Watt ran the Interior Department under President Reagan from 1981 to 1983 with profound hostility toward environmental causes. He opened almost all of the United States’ coastal waters to drilling, increased industry access to coal on federal lands, and made it easier for corporations to strip-mine. He resigned two years into his appointment after making an offensive remark about the identity of people on the panel reviewing coal-leasing policies, but not before Trustees sued him.

The 1982 James Watt portrait in the National Portrait Gallery by artist Mark Hess. Notably, Time magazine did a riff on this image on the Aug. 23, 1982, cover with the headline, “Going, going…! Land Sale of the Century.”

The lawsuit represented Trustees’ first major legal challenge to federal actions threatening the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. It charged Interior and Watt with violating the National Wildlife Refuge Administration Act and Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act by transferring part of the management of the Arctic Refuge from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to the U.S. Geological Survey.

ANILCA prohibited drilling for oil and gas in the Arctic Refuge without additional congressional action, but allowed a seismic study of the coastal plain by the Interior Department. Watt ordered that USGS, rather than USFWS, be “lead agency” for the seismic study.

Mintz, who was the executive director of Trustees at the time, said it was a strong case because there was already a provision of federal law that said that USFWS would manage refuges. “We brought the lawsuit and won on summary judgement,” he said. “They appealed to the Ninth Circuit, and it was pretty cut and dry.”

The Ninth Circuit court of appeals would come to Alaska once a year to hear cases, and this was one of them. Trustees had requested declaratory and injunctive relief and that the court vacate Secretary Watt’s transfer of lead agency authority . At one point, the presiding judge on the panel said, “Mr. Mintz, aren’t you asking for preventive medicine?”

The night before, Mintz had by chance gone back and looked at his law school casebook on injunctions. “Your honor,” he said, “that’s what declaratory and injunctive relief is all about.”

He remembers the judge smiling. Trustees won the case.

An accumulating impact

In that first decade from 1974 to 1983, the Trustees team was small, but the need was huge and there were many issues on the hot plate.

Rice says Trustees got involved in the effort to stop oil and gas drilling in Kachemak Bay back in the mid-70s. A contested lease sale in Kachemak Bay pit Outside oil and gas companies against local fisherman and became part of a political fight through which Jay Hammond became governor. In a rare but pivotal decision, the Alaska legislature voted to buy back leases in 1976 after a rig got stuck in the mud and spilled oil in the bay when Shell Oil tried to move it. As a result, Kachemak Bay continued to be a place for fishing, traveling, and recreating rather than an area dotted with oil rigs.

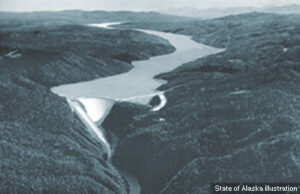

A State of Alaska rendering of the proposed Susitna dam.

There was also a big push to build a dam on the Susitna River with potentially disastrous impacts on salmon and other marine life. Trustees challenged the Alaska Power Authority’s approval of the Susitna Hydroelectric Project before the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. The proposed methods of paying for the project were unconstitutional, said Rice, and would have cost billions. The dam was never built.

Plenty of other legal actions and litigation took place around placer mining and oil and gas development, said Eric Smith, who started as executive director in 1982.

The latter part of the decade brought opportunities for building relationships as well. A regional group in Bethel called Nunam Kitlutsisti asked Smith to visit the region in 1983 as part of its efforts to protect the Tuluksak River from oil and gas activities. It was an early step in Trustees’ ensuing effort to help build and support coalitions with sometimes unlikely partners.

Smith, who stayed with Trustees until 1986, marvels at the current staff of 14 at Trustees. “I’m always bemused and amazed and happy that Trustees got so big,” he said. “When I was there it was me, a staff attorney, and a half-time secretary.”

Trustees has grown in more ways than one. The need always get bigger and the workload, too, as the small but mighty law firm continues playing a part in protecting places important to Alaskans and their ways of life.

Up next in our 50th anniversary newsletter series, we’ll talk about Trustees’ landmark cases over the last 50 years. Here is the first story in our 50th year series.