We argued in Ninth Circuit Court to protect Izembek & all national parks and refuges in Alaska

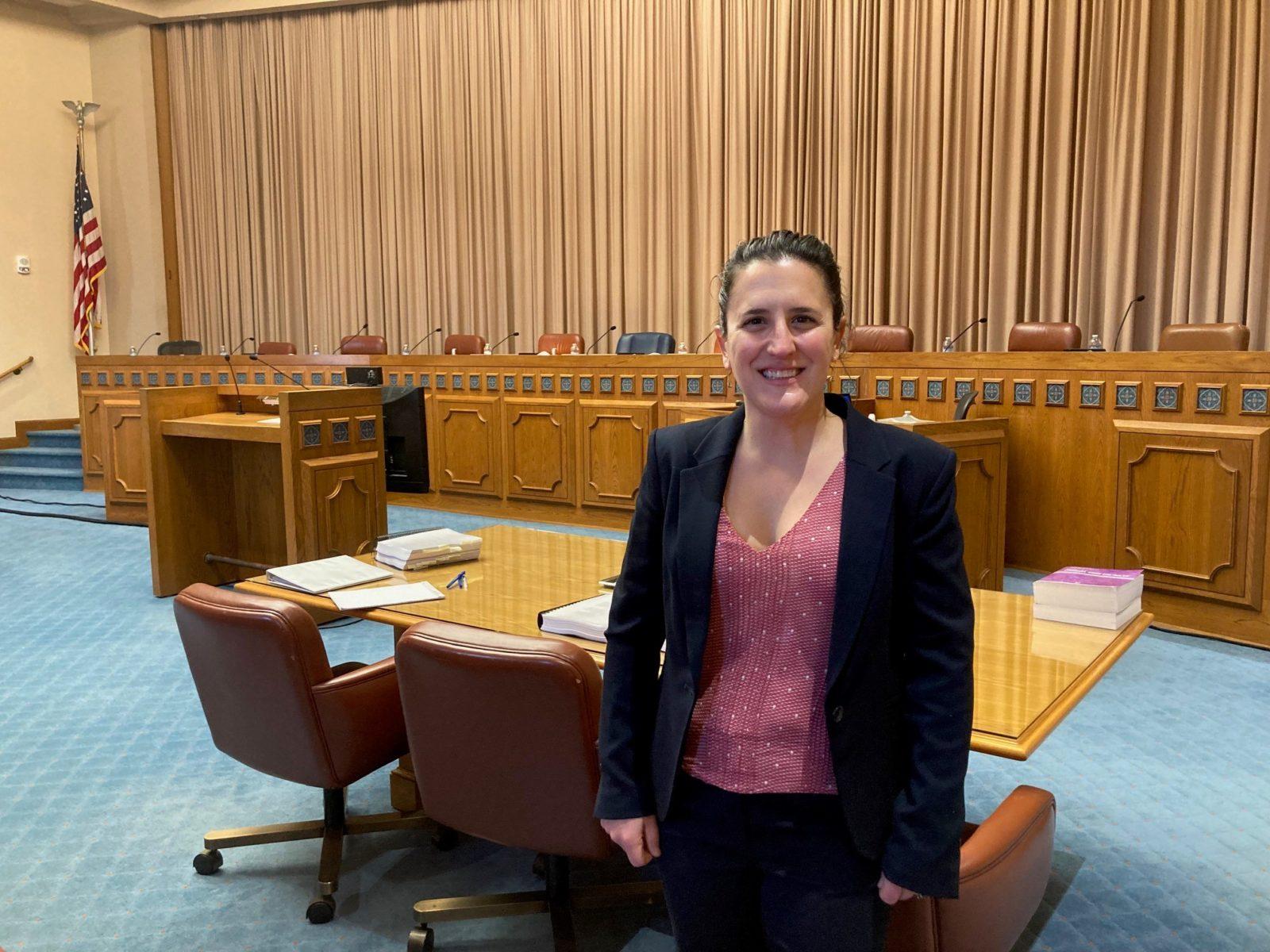

Yesterday, on a sunny December afternoon in Pasadena, California, we argued before a full panel of the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals to protect national parks and refuges in Alaska, and to uphold the integrity of a law intended to conserve these lands and the subsistence uses of them. We’ll talk about the oral argument soon, but we first want to overview what’s at stake.

The hearing centered on a 2019 land exchange made between Interior Secretary Bernhardt and King Cove Corporation to make way for a road in Izembek National Wildlife Refuge, an area that’s natural values are so important that Congress designated nearly the entire refuge as Wilderness with the protections that designation includes.

Commercial interests have advocated for the road for decades to benefit corporations and allied businesses that process and transport fish, among other potential activities.

The road would threaten the health of a narrow isthmus and internationally-recognized wetland region that supports an array of birds, fish, and animals important to the refuge and nearby communities.

Most troubling of all, allowing an unelected Interior secretary to trade away congressionally designated Wilderness areas without public transparency or congressional approval would mean ignoring and undermining the purposes outlined within the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980 and the particular refuge statute itself.

It would also mean opening the door to an array of activities on national parks and refuges—things like mining, airports, etc.—with devastating long-term effects on public lands.

Izembek in court, a quick review

Economic interest in a road through Izembek is many decades old, but the land swap deal in question occurred during the Trump administration. Two Trump-era land swaps were penned; we took both to District Court and won.

Interior appealed the latter 2020 District Court decision, and the Biden administration continues to defend it.

In March 2022, a small panel of the Ninth Circuit Court issued a 2-1 ruling allowing the land swap. We quickly filed an en banc petition requesting a full Ninth Circuit Court review due to the dangerous legal and on-the-ground consequences of the ruling—namely, that it would let an Interior secretary reverse decades of agency policies with no or deficient explanation in order to commercialize and privatize areas Congress set aside to conserve for future generations.

Last month, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals vacated and granted a rehearing of that March 2022 ruling. (Read more about why we filed that petition and what it means in our litigation 101 series.)

A dive into our oral argument

The hearing covered a lot of ground, with many questions from the panel of 11 Ninth Circuit Court judges. We continued to argue, as we have in all hearings, that Secretary Bernhardt’s land swap undermines ANILCA’s conservation and subsistence purposes.

ANILCA allows an Interior Secretary to acquire lands by exchange to further the purposes of ANILCA; it does not allow the Secretary to trade lands for any purpose they choose or based wholly on social and economic interests.

Congress undertook a thorough, intentional, bipartisan effort to set boundaries for national parks and refuges, designate particular areas as protected wilderness, and explicitly describe the conservation and subsistence purposes of these lands. ANILCA balanced these purposes with the social needs of Alaskans by including provisions clearly aimed at allowing transportation systems through these protected areas; the agencies just need to follow the process Congress laid out in Title XI.

To suggest that an Interior appointee can shrug aside ANILCA’s clear and balanced guardrails to give away protected lands for economic development would mean turning ANILCA into a suggestion.

In other words, we argued that the court should not read statutes to give more authority to an appointed secretary than to Congress. We further explained that the small acquisition provision within the act doesn’t give the Secretary power to rewrite national park, refuge, and wilderness boundaries.

The Supreme Court’s opinion in the Sturgeon case rejects an interpretation of ANILCA that throws its carefully and congressionally drawn balance of purposes off kilter, as we explained in court.

And then there’s the facts

We further argued that when then-Secretary Bernhardt claimed that there were no alternatives to providing transportation for health care to King Cove without a road—and that therefore swapping land to make way for that road was justified–he ignored the fact that there are alternatives. In fact, the 2015 report he used to make this claim concluded that air and marine transportation would be cheaper and safer than a remote gravel road.

It’s important to say, too, that weather and other hazards would make driving dangerous, deadly, or even impossible.

Moreover, his claim of entering a land deal for the health of Alaska Native communities failed to consider impacts to communities other than King Cove, and never mentioned the roughly 50 villages that opposed a land exchange in 2013. Indeed, the 2022 Hooper Bay amicus brief opposes Bernhardt’s land swap because of its impacts to their food sources and subsistence activities.

In other words, the Secretary’s land swap violates the Administrative Procedural Act by first reversing policy without adequate analysis and explanation to justify that reversal, and second by falsely claiming that swapping land in Izembek for a road best serves the social and economic needs of all Alaska Native communities.

What the future holds

Truth is, there are careful processes for seeking a road through national parks and refuges, and the Bernhardt land swap attempts to skirt them. It attempts to turn a law intended to protect public lands into a way to quickly redraw park, refuge, and wilderness boundaries however the next Interior secretary desires.

Many Alaska communities lack roads and road access to other communities or highways. The state and federal governments, together with others, can support and fund transportation alternatives that have been shown to be safer and cheaper.

The real question in this case is how do we ensure public land protected by law, i.e., ANILCA, is truly protected if an Interior Secretary appointed by the President can gut those protections through a backdoor deal made with private interests without oversight or public process?

The answer is we can’t.

The answer is that Interior secretary after Interior secretary would use land swap after land swap to allow industry and commercial interests to erode the places set aside in Alaska by Congress to conserve and protect.

That’s what’s at stake, and that’s why we fight to protect Izembek and all national parks and refuges in Alaska.