Wildlife management or managing ourselves—a look at predator control practices in Alaska

By Madison Grosvenor

Last month, the Alaska Wildlife Alliance secured a major victory in court for Mulchatna brown bears. The Alaska Superior Court ruled that the State of Alaska’s bear control program—responsible for aerially gunning down nearly 200 brown bears—was unlawfully adopted. The decision comes after years of aggressive predator control—also called intensive management—efforts led by the Alaska Board of Game, often decided and carried out with little regard for scientific data.

Brown bear walking in Katmai National Park and Preserve. The State’s Mulchatna predator control program threatens the lives of bears that use the park. (Photo by F. Jimenez / National Park Service)

Yet, after the ruling struck down the program, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game petitioned the Alaska Board of Game to adopt an emergency regulation reinstating the predator control program. The Board of Game gave less than 24 hours’ notice for public testimony for its meeting the following morning. Despite the recent ruling that the program was unlawful, along with extensive public opposition, the board passed the “emergency” regulation that allows the state to kill bears and wolves this spring. As it currently stands, the aerial gunning of Mulchatna bears will recommence in May.

How did we get here

The Mulchatna program is just the latest chapter in Alaska’s long and contentious history of predator control programs. In 1994, the state passed the Intensive Management Law, which mandates increasing populations of moose, caribou, and deer for human consumption. Where prey populations—primarily moose and caribou—aren’t considered robust enough to meet hunters’ demand, the Board of Game cannot reduce bag limits unless it also implements intensive management programs. While intensive management includes habitat improvements and regulatory changes, the Board of Game has relied heavily on predator reduction, greatly favoring aerial gunning and large-scale slaughter to suppress wolf and bear populations. Most research shows this approach does not work, yet the Board of Game continues.

New York Times Article discussing the debates surrounding wolf-killing following the Wolf Summit in Fairbanks, 1993

This approach is nothing new. From state-sponsored wolf bounties in the 1990s to modern-day aerial shooting programs, predator control in Alaska has been shaped by a persistent narrative: that wolves and bears stand in the way of game abundance.

But who decides how many predators are “too many”? And what does the science say about these management choices?

To understand where we are now, we first have to look back at the long, often brutal history of predator control in Alaska.

Welcome to the intensive management vocab lesson

In 1994, the Alaska State Legislature authorized Senate Bill 77, “An Act Relating to the Powers of the Board of Game and to Intensive Management of Big Game to Achieve Higher Sustained Yield for Human Harvest.”

Alright, let’s break this down, because Alaska’s Intensive Management Law is a weird, tangled mess of words and wildlife politics. The biggest issue? Sustained yield vs. maximum sustained yield—two phrases that sound similar but have wildly different meanings.

The Mulchatna caribou herd at the Telequana Corridor in Lake Clark. Photo courtesy of NPS.

The Alaska Constitution established that “Fish, forests, wildlife, grasslands and all other replenishable resources… shall be utilized, developed, and maintained on the sustained yield principle… subject to preferences among beneficial uses.” At its core this means don’t harvest wildlife at a rate that drives them to extinction. Simple, right? It’s about ensuring animals—moose, caribou, wolves, bears—are managed in a way that keeps their populations stable over time.

However, when the Intensive Management Law was being debated, then Lt. Gov. Jack Coghill took a different approach. That’s where ‘maximum sustained yield’ sneaks in.

Coghill insisted the clear meaning of sustained yield “was for replenishable resources to provide a high or maximum sustained level of consumptive utilization for humans”. Basically, treating moose and caribou like cattle that need to be farmed for hunters. The legislature ran with it, defining sustained yield as maintaining “a high level of human harvest,” which is a big leap from the original concept.

Maximum sustained yield is a theory. Perhaps one akin to the goals of farming. Yet, nature isn’t a factory assembly line. Populations fluctuate, habitats change, weather changes year to year and oh yeah, predators exist. You can’t just pump out an endless supply of moose while trying to erase wolves and bears from the landscape.

Even Alaska’s courts have determined that predators also need to be managed for sustained yield (meaning: don’t wipe them out completely). But then made quite the logic jump, deciding that since the constitution allows for “preferences among beneficial uses,” the Legislature could legally prioritize moose and caribou by slashing predator numbers to the bare minimum.

Black bears napping in a tree. Photo by Laurie Craig, ADFG.

It’s a legal loophole that turns wolves and bears into collateral damage for a game farm-style approach to wildlife. (And as we’ll see later, this approach doesn’t even achieve its own goal.)

This is where things get even messier. The same word games that skewed sustained yield also warped the definition of subsistence. The state and federal governments define “who is a subsistence user” very differently, leading to confusion and conflict over hunting regulations. Under Alaska law, all residents are considered subsistence users, meaning any Alaskan can hunt under state subsistence regulations regardless of where they live. This broad definition treats urban and rural hunters the same, prioritizing maximum hunting opportunities across the state.

Sandy Rabinowitch, a retired National Park Service member of the Staff Committee to the Federal Subsistence Board, said in the realm of predator control, state and federal definitions continue to clash.

Federal law defines subsistence users as only rural residents who have a customary and traditional use of the resources. Thus, on federal lands, federal subsistence hunting is managed by the Federal Subsistence Board, which ensures rural communities have priority access for hunting under federal regulations. These conflicting word games effectively blur the line between subsistence for survival and sport hunting, opening the door for policies that prioritize higher game populations for all hunters—at the expense of predators.

And the not-so funny thing? At least for the IM Statute, hunter demand is one of several criteria that determines the harvest objective. Not science.

So, here we are: a law that twists words to justify shooting wolves and bears from helicopters, all for a misguided attempt to ensure more moose and caribou for sport hunters. It’s wildlife management through a funhouse mirror. Science takes a backseat to politics and anecdotal stories, and definitions get bent to fit an agenda.

The State’s sleight of hand

This legal and linguistic sleight of hand didn’t just appear out of nowhere, it’s the result of decades of policy shaped by the Alaska Board of Game.

Wolf looks up from tundra. Photo courtesy of Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Since the passage of the Intensive Management Law, the Board has taken an increasingly aggressive approach to predator control, leaning heavily on lethal measures like aerial gunning and large-scale killings.

The Board initially struggled with implementing the intensive management amendments in a rational way, but Governor Frank Murkowski, who took office in 2003, made changes that drastically altered its membership to heavily include people who supported aggressive predator control programs that included huge bag limits, longer seasons and relaxed hunting methods, and allowed people to shoot wolves out of airplanes.

Once such program was the State’s institutional effort to kill wolves and bears under then-Governor Sarah Palin. This included a $150 bounty for each left foreleg of wolves killed through aerial hunting, notably disguised as a “State Incentive Program.” Trustees challenged the program in court in 2006, securing a halt to bounty payments, though the court upheld the state’s interpretation of sustained yield. In 2009, Trustees appealed, arguing that Palin’s predator control programs violated the Alaska Constitution.

Despite these challenges, the courts ruled in favor of the Board of Game in 2010, allowing aggressive predator control to continue on state lands—once again targeting predators as an ‘easy fix’ while expanding sport hunting, including trophy hunting interests.

Jurisdictional tug-of-war

Wildlife management in Alaska is somewhat of a jurisdictional maze, shaped by both the Alaska Constitution and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act or ANILCA.

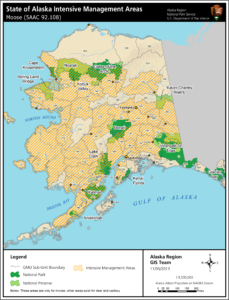

Map of the State of Alaska’s intensive management areas. Courtesy of NPS and Sanford Rabinowitch.

While the state prioritizes maximizing game for hunters through predator control, federal law emphasizes the natural dynamics between animals, or . This ongoing clash between state and federal authority has led to decades of legal battles, conflicting policies, and disputes over who ultimately decides how Alaska’s predators are managed.

At statehood in 1959, Alaska assumed control over its wildlife, with the state managing both game and subsistence hunting. However, with the passage of ANILCA in 1980, the federal government reasserted authority to manage a significant portion of Alaska’s lands, including national parks, monuments, wildlife refuges, BLM lands and U.S forest lands creating a legal framework of federal oversight, which took priority when state policies conflicted with broader federal conservation goals.

On top of Alaska’s intensive management policies, the State’s liberalized hunting methods have long clashed with federal conservation mandates, creating tension where the state prioritizes boosting game populations while some federal agencies strive to protect entire ecosystems. This conflict escalated in 2015 when the National Park Service and the Fish and Wildlife Service adopted regulations banning extreme predator hunting practices. The National Park Service banned practices—such as baiting bears, spotlighting dens in order to kill sows and cubs, and killing wolves during denning season—on national preserves, and the Fish and Wildlife Service banned brown bear baiting on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge.

In 2017, the State filed a lawsuit to dismantle the Parks Service regulations. Trustees intervened on behalf of several conservation groups to defend regulations protecting wildlife in the national preserves and refuges

Later that year, two memos from the Department of the Interior instructed Park Service and Fish and Wildlife to redo the regulations to undo protection of bears and wolves on national preserves in Alaska. Again, we went to court.

Female brown bear and her cubs of the year in Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. Photo by Madison Grosvenor, 2024

In November of 2020, Trustees got a major win in litigation challenging the Fish and Wildlife Service regulations when the court upheld the prohibition of brown bear baiting in the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. The ruling confirmed that, under ANILCA, Fish and Wildlife Service preserves the authority to regulate wildlife hunting practices on national wildlife refuges according to federal mandates, even if in conflict with state regulations.

The State doesn’t like that the federal government gets to call the shots on federal land and has long cried ‘federal overreach’ when required to adhere to federal mandates on wildlife management.

“There’s this tension between the two that hasn’t gone away since 1980 when ANILCA was signed into law by President Carter,” said Rabinowitch.

This tug-of-war goes on.

The tables turn

In June 2020, during the first Trump administration, the Park Service reversed decades of policy and handed the Alaska Board of Game free rein to roll out extreme predator-killing tactics on national preserves. This reversal marked a major shift—the Park Service abandoned its longstanding position that Alaska couldn’t impose sport hunting rules designed to kill predators like wolves and bears to boost game populations.

Coastal wolf in Katmai National Park & Preserve. Photo by D. Kopshever.

The rule change greenlit hunters to shine artificial lights into dens to shoot hibernating bears, bait brown bears with piles of doughnuts and grease, and kill wolves and coyotes (along with their pups) during denning season. For years, the Park Service had pushed back against these methods, recognizing them for what they were: blatant attempts to manipulate wildlife populations to benefit sport hunters and intensive management goals of high human harvest. But this wasn’t just a policy tweak—it was the agency flat-out abandoning its duty to protect wildlife on federally managed lands.

We sued the Park Service that August, alleging that the agency failed to comply with its legal obligation to protect wildlife diversity on national preserves, violating the Organic Act, ANILCA, and the Administrative Procedure Act.

Again, while the State generally manages sport hunting on federal lands, federal law controls where state regulations conflict with park purposes. During this period, the Park Service allowed an array of destructive hunting tactics, violating its own mandates in the process.

In 2022, the U.S. District Court ruled that the 2020 rule was poorly reasoned and arbitrary, sending it back to the Park Service to fix. Instead of scrapping the rule, the court let it stay in place while the agency rewrote the rule.

Unfortunately, the Park Service ended up finalizing a rule that proved, well, underwhelming. While it finally prohibited bear baiting, the agency adopted a 2024 rule that acknowledged its authority to prohibit various brutal hunting practices yet did not explicitly prohibit them in stark contrast to the position it took with its 2015 hunting rule.

Bear den on Dumpling Mountain in Katmai NP&P. Photo courtesy of NPS.

Hunters killing black bear cubs and sows with cubs using artificial light at den sites. Killing wolves and coyotes—including pups—during denning season? Still legal. Using dogs to hunt black bears? Allowed. Shooting swimming caribou or hunting them from motorboats under power? Not prohibited.

With this rule, the Park Service acknowledged it had the authority to prohibit these practices but chose not to.

Instead of taking a stand against liberalized hunting practices designed to target predators, the federal government rubber-stamped a half-measure, leaving key predator species open to slaughter in favor of boosting game populations. The message was clear: politics vanquished science, conservation, and the very mandates of laws meant to protect our national preserves.

This 2024 rule inexplicably failed to prohibit troubling state-sanctioned sport hunting practices aimed at cherry-picking predators in favor of prey species.

History repeating itself

Brown bear paws in Katmai National Park and Preserve. Photo by Kaiti Critz, NPS.

Today the past is happening again. The State of Alaska is charging ahead with its unlawful “intensive management” program for a third year, still clinging to the misguided claim that killing predators will somehow revive the struggling Mulchatna caribou herd.

Under the plan, Fish and Game staff and contractors fly over nearly 3,000 square miles of the Tikchik Basin, gunning down every wolf, black bear, and brown bear they see—no matter their age, their sex, whether a sow with cubs, or any other factor.

Since the Mulchatna predator control program launched in 2023, nearly 200 bears and 19 wolves have been killed. Yet, the Board of Game has no reliable estimate of how many bears even live in the area and therefore have no way of knowing what impact this mass killing will have on these bears or the surrounding ecosystem as a whole.

These brutal policies highlight the contradictions of drawing lines across wild landscapes.

“Animals have legs. They don’t know where these lines are, and they certainly don’t read the hunting regulation book” said Rabinowitch. “A wolf or bear protected in one park or refuge might unknowingly cross into a game unit where predator control is in full swing.”

In the case of Mulchatna, game units 17 and 18 sit just outside Katmai National Park—federal land where brown bears are not only protected from predator control but have become accustomed to the presence of thousands of park visitors each year. The moment they wander past some invisible boundary, they become targets, shot from the sky in the name of “management.”

The patchwork of state and federal lands across Alaska where the state prioritizes killing predators to boost game while federal agencies protect entire ecosystems fuels ongoing battles over the fate of Alaska’s wildlife.

Coastal brown bear walks by a float plane in Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. Photo by Madison Grosvenor, 2024.

More to the point, it presents a scientific and ethical crisis.

Killing predators like wolves and bear on a mass scale without knowing the population size isn’t management—it’s recklessness and a set-up for disaster. Ecological research shows that ecosystems depend on predators to stay healthy and sustainable, yet the State of Alaska ignores these known facts in favor of outdated, unproven ideas about boosting caribou and moose populations that not only fail, but put all these animals at risk

Ethically, the contradiction is just as stark: How can we justify protecting predators in one place outlined in human maps while wiping them out once they cross a line that doesn’t exist for them? If wildlife management ignores science and common sense, what interests are guiding these decisions? Isn’t “wildlife management” really about managing ourselves?

We’ll explore these questions next month in the second part of our series on wildlife management in Alaska.