Drinks with lawyers: Geoff finds work that matters

By Dawnell Smith

The summer after third grade, Geoff Toy joined his family on a trip to Glacier National Park where they learned about the return of wolves. The animals had been exterminated from the park for about 50 years when a pack from Canada showed up in the 1980s. It turns out that the Endangered Species Act helped keep them there.

Geoff in Glacier Bay National Park, 1996. Family photo.

“I remember my mom turning to me after that talk and saying, ‘that would be a cool career for you to think about,’” said Geoff, alluding to legal work.

It was 1996, and Geoff was a kid with a smash of red hair and a long way to go before making career decisions, but his mother’s comment nudged him gently on the “what are you going to do when you grow up” question. His mom Jeanne Thomasson doesn’t remember saying it, but Geoff does—because that trip and her words put the law and lawyering on his radar for the first time.

What Jeanne does know is that lawyering has taken Geoff thousands of miles from his home in Atlanta to Alaska to practice law and she’s not thrilled about it. But she understands how he got there.

“Some folks say that the surest sign of a young lawyer is a propensity to argue all the time,” said Jeanne. “That would not be the case with Geoff — quite the opposite, in fact.”

Geoff wasn’t argumentative as a kid, but he always had “a tremendous facility with language,” she said, and an “uncanny ability to understand and articulate his own feelings, and to perceive others’ feelings and motivations.”

He was the kind of kid who considered things before doing them. If set down in front of a big mountain, she said, Geoff wouldn’t begin to climb it “because it’s there,” he would take a long look and “consider the altitude and the angle of the slope, the cost of the equipment and the time it would take, the danger and likelihood of success, and whether there’s anything up there that he really wants anyway.”

He might after all that forethought decide it’s not worth the risk or effort and turn and walk away, but he might decide to climb that mountain and if he did, she said, he wouldn’t quit. He’d stick with it. He’d persevere.

“What else would you want in your lawyer,” she said, “except someone who’ll be straight with you about your chances, and if he takes up your cause will never lay it down?”

Curiosity thrills the cat

Another thing you need to know about Geoff is that he always wants to know more. What he learned about wolves on that Glacier trip as a kid stays with him even now in a vastly more expansive way. Wolves play an important role in helping keep balance among a multitude of plants and animals in relationship with each other—they belong—and that understanding has informed his broader perspective about nature, animals, and the world, how everything’s interconnected.

Learning is how Geoff got into law, and it’s also what practicing law gives him every day. In his first few months with Trustees, Geoff dove into Alaska-specific laws and immersed himself in their context and implications. Several of these laws post-date the laws in the Lower 48, and seem to have learned from them, he said, and avoid putting a priority on extraction only. Geoff has also worked on multiple issues from hunting regulations to oil and gas extraction projects in the Arctic.

“I like getting to tackle complicated problems working with scientists and Indigenous experts, and constantly learning things,” he said. “That’s what legal work is—a new problem, a new case, a new solution. You learn everything you can and synthesize what will get the court’s attention.”

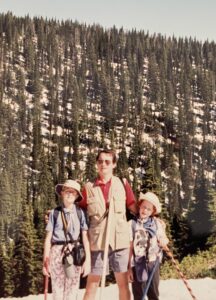

Geoff with his dad and sister in Glacier, 1996. Family photo.

With the learning comes the teaching—there’s the part where you figure out the legal angle and the part where you help the court understand it too.

His wife Caroline Crowell said Geoff has always been curious, always wanted to know how things work and why, always wanted to dig for one more fact or piece of knowledge before finishing a project or paper. He also likes to share and teach, she said, whether informally when he’s the environmental law expert in the room or after law school when he taught law students during a fellowship with Emory.

She first met him at an archery club gathering in college. “My first memory of Geoff was watching him teach other college students how to shoot a bow and arrow (both safely and successfully!) and admiring how he went about it,” she said. “Teaching something that is fundamentally dangerous without removing all the enjoyment requires walking a fine line of rules and camaraderie, and Geoff was great at it.”

A woodland life in the burbs

Geoff grew up in Atlanta in a house that backed up to the floodplains along the Chattahoochee River. He’s young enough to remember the arrival of the family’s first computer and old enough to remember there wasn’t a lot you could do with it. He spent his days outside, playing and exploring near his home.

“I had a more outdoorsy upbringing in the woods than it seems you could in the suburbs,” he said.

His family traveled a fair bit and that appealed to his sense of wanting to see and understand the world and to his connection with nature. He graduated from high school in 2006, the same year “An Inconvenient Truth” came out and from Kenyon College the same year the Deepwater Horizon blew.

Geoff and Caroline on Cumberland Island, Georgia, 2022.

He knew early on that “climate change would be the issue of my time” and that the health of natural places mattered to him.

You might say all arrows pointed at environmental advocacy as a natural progression of Geoff’s young adult life, but after graduating with a degree in medieval history at the tail end of the Great Recession, he decided to make and save some money, so took a job as a cook and server at a “living history” medieval village outside of Seattle.

“We had to call people m’lord and m’lady,” he said, “which proves that, yes, you can find jobs with a medieval history degree, it’s just that they’re going to be weird.”

He worked at a factory and tried other ways to make a living, but none made him feel like he was doing anything that mattered, so he headed back to Atlanta to attend Emory Law School.

Back to the books

Law school suited Geoff in terms of its centering of language, knowledge, and particularly in how he could help take what he learned and apply it in the world. He got involved with Emory’s environmental law clinic, which had one program where it partnered with the Working Farms Fund to protect lands with conservation easements and lease the land back to farmers. The idea is that the Fund would buy farmland within 100 miles of Atlanta, permanently protect it from industry and anything harmful to the environment, and then lease the land back to farmers with a path to ownership. First-generation farmers benefited by getting a path to land ownership while Emory achieved several of its goals, including protecting land and providing a means for getting local produce and supporting local farmers.

For Geoff, the “win, win, win” of this endeavor demonstrates how dynamic environmental law can be. “You can touch so many things doing this work,” he said. “It’s about the water, our food, how power is generated, about air, about climate change, about health.”

The intersection and interconnection of so many systems and challenges make practicing environmental law rewarding and compelling, he said.

“When you look at something like the proposed Pebble mine, you of course see the impact it would have on fish, but there would also be the emissions from transportation and social and health impacts on people,” he said. “The impacts of a project or decision are always bigger than it first seems.”

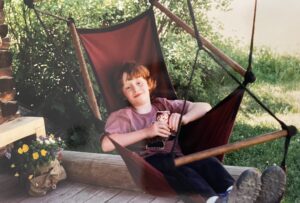

Geoff chilling out in Glacier National Park, 1996. Family photo

Not all legal practices work that way. Geoff spent time doing legal work on car accident cases, where the legal piece is exactly as it seems, he said. There may be a compelling human story leading up to or in the aftermath of an accident, and he learned a lot about managing cases with that work, but it’s not his calling.

To be clear, Geoff didn’t always know he wanted to be an environmental lawyer, “but I always wanted to be involved in the environmental movement.”

Now he’s doing just that. He’s working with laws unique to Alaska—the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act—in an arena of groups and people advocating for the health of land and water, fish and caribou, and climate and biodiversity. There’s an expansive community purpose to this work, and doing it feels impactful, he said.

What’s hard is seeing how divided people and communities can be on environmental issues and knowing how much fear plays a role. There are good reasons to fear industrialization, pollutants, dam failures, oil spills, and climate change, and there’s also good reason to fear losing or not being able to find a job to take care of one’s family.

The issues easily become either/or debates when they don’t have to be, but that’s how it ends up feeling for people, and lawyers end up in the middle of it.

Alaska state of mind

Geoff and Caroline fell in love with Alaska within a year of his start at Trustees in September 2022. They love the night sky and the Northern Lights, and the bigness and vastness of even just the area near Anchorage. They’ve become avid aurora borealis hunters who pay attention to a tracker app so they can drive south to Beluga Point or north to the Matanuska Lakes for clear views. They bought a house.

Geoff expected the snow and cold and aurora borealis because those things go with any story of the state. What surprised him—and perhaps drew him in—about Alaska is how it has a “slower pace of life than Atlanta and Seattle where I’ve lived before and where it felt like ‘go, go, go’ all the time, with lots of traffic, lots of construction going on, a ton of focus on money. In Alaska, you don’t sit in traffic packed across multiple lanes for hours. People here seem to value being outdoors more, they value the time they have in nature. There’s a philosophical difference in how they relate to where they live.”

When it gets cold in Georgia, people stay inside, he said, but here, “people do things outside all the time as if it’s not freezing.”

He and Caroline have a bucket list of places they’d like to see, and things they’d like to do. Geoff would love to camp or hike in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and go to Gates of the Arctic National Park and western Alaska.

For now, though, he’s on the lookout for his next professional leap. His fellowship ends in the fall of 2024, so he’s paying attention to potential opportunities. He’d like to continue doing environmental work, and even possibly work for the government someday, “because if we’re going to address climate change in a real way, government will have to make it happen,” he said.

Another thing about Geoff, says his dad Peter Toy, is that he “has been an eloquent and logical debater from an early age, and he is also very resilient handling disappointment.”

Geoff and Caroline in Denali National Park, fall of 2022. Photo by passerby.

Aurora activity may be high as the clouds roll in; a legal argument may be sound when the court rules against it; a role may be perfect even as it comes to an end. The way Geoff sees it, you need to keep a perspective that under

stands the nature of getting things done. There are setbacks along the way and paths that open up despite and even because of those setbacks.

With legal work, you must understand the role of a lawyer and the law in a larger movement, he said, “and ask questions that achieve the larger goals.”

“What does it mean to win? What does victory look like? Sometimes you can lose a case, but get the attention and the backing to reach the outcome you want,” he explained.

Perseverance helps, the resilience to bounce back from disappointment, an ability to hold onto the view of the forest while tangled in trees.

There’s a lot to care about and a lot of people caring about it. Geoff said that one of the things he loves about working as an attorney is knowing “that other lawyers are working for justice across the board, for gender justice, for racial justice, for reproductive justice, and so on.”

The knowledge that all those attorneys are out there, working with communities, advocates, Tribes, groups, and people gives him hope. It keeps him focused, inspired, and engaged.

“The practice of law is a means to an end,” he said, “and that end is a world that’s a better place.”

This is the sixth in a series of profiles based on interviews with Trustees’ attorneys over drinks, this time over samples of cider at Double Shovel Cider Company in Anchorage.

More in the “drinks with lawyers” series:

- Joanna makes it to the big leagues

- Lydia’s quarter-life crisis

- Rachel makes a case for shiny red shoes

- Katie on going into the unknown and being the smaller animal

- Bridget on doing good and paying the bills