Protecting Salmon Streams from Chuitna Coal Mine

At the headwaters of a tributary to the Chuitna River, called Middle Creek, is one of the most significant salmon and climate fights in this country—and you probably haven’t heard about it. The Chuitna River, running from the foothills of the Todrillo Mountains, is about 45 miles across Cook Inlet from Anchorage. It is a pristine watershed, supporting all five species of wild Pacific salmon and providing for sustainable and productive subsistence, commercial and sport fisheries.

Miles of wild salmon streams will be destroyed by the Chuitna Coal Mine. Photo courtesy of Alaskans First.

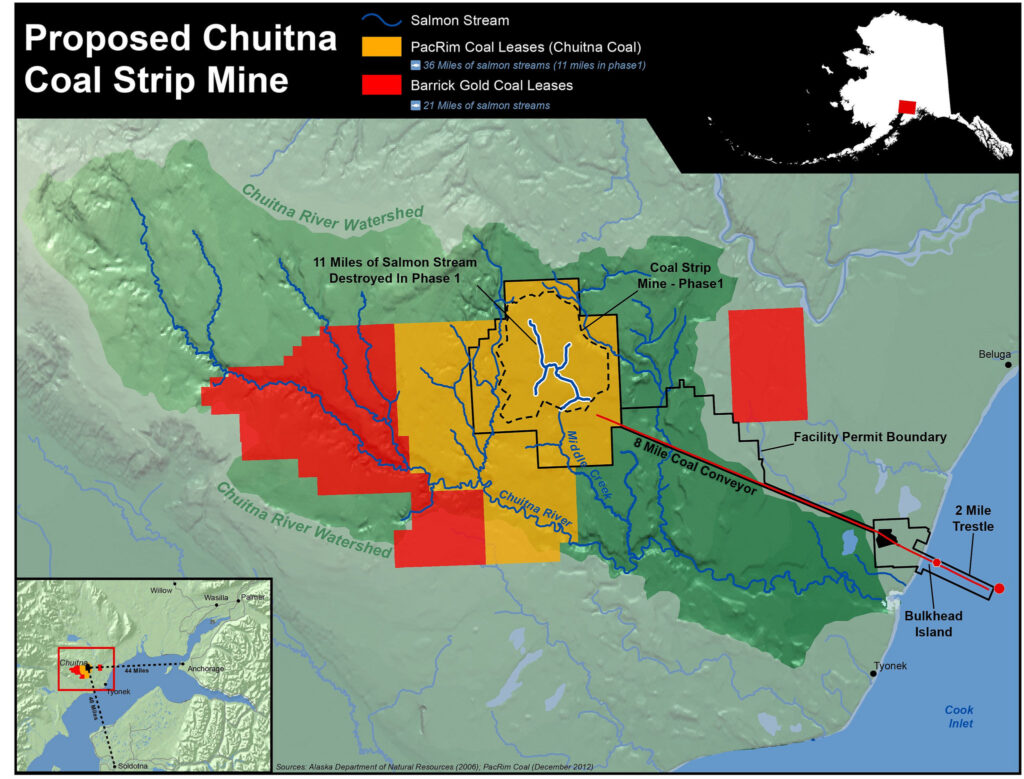

The headwaters of Middle Creek lies smack dab in the middle of PacRim Coal’s proposed massive strip coal mine. The project would mine for coal over 5000 acres, making it the 14th largest coal mine in North America and the largest coal mine in Alaska. The mine’s coal reserves total approximately 300 million metric tons of bituminous (low grade) coal.

The mine plans include destroying over 14 miles of the Middle Creek, a salmon bearing stream, and 1361 acres of high-functioning valuable wetlands that provide rearing and over-wintering habitat for fish. To get to the coal PacRim must dig 300 feet down to the existing coal seams, which lie directly beneath Middle Creek. As a result, PacRim will completely unearth and destroy the salmon stream and dewater (dry up) all the surrounding surface and groundwater to get to its coal. This would be the first project to mine directly through salmon-bearing streams.

Stream Restoration?

PacRim says it can rebuild the stream but the existing science just doesn’t support this proposition. There is not a single example of rebuilding a salmon stream from scratch in a northern environment. Rebuilding streams to support salmon is more than digging a new ditch when the mining is over several decades from now. The underlying ground water and surface water hydrology would need to be restored by PacRim, from plankton and insects up to salmon swimming and spawning once again in the stream. This is a tall order.

Nothing in stream restoration has been achieved anywhere near what PacRim claims they can do. In fact, much simpler projects, where ground and surface water were not impacted, have proven to be tricky, failing more often than not. PacRim was formed just for this project. Once the profit is extracted, it is unlikely the company will have the financial resources to complete any remaining needed repair of the mine site, leaving the government to try and salvage the salmon run.

If You Build It, They Will Mine

Destroying salmon streams isn’t the only significant and precedent-setting problem here. PacRim holds leases for two other designated mining units, totaling over 20,000 acres or about 30 square miles. Once PacRim gets the requisite permits to begin phase 1, it will need to invest over a billion dollars to build the infrastructure to export coal.

There are no roads to this area on the west side of Cook Inlet. Getting the coal out of the ground is only part of the story. PacRim plans to construct an eight-mile-long conveyor from the mine area to Cook Inlet. Then build a trestle extending two miles out into Cook Inlet. Additionally, PacRim will build roads, a landing strip, and a massive logistics site to store coal. It also will build an entire island just offshore to address the numerous logistics problems that come with mining in an area that can only be accessed by air or water.

Financing such an expensive project for the first phase of the project means that once the infrastructure is completed, PacRim will be eager to develop coal from its other two mining units. When considering all of PacRim’s leased mining area, it would destroy at least 36 miles of salmon streams. It would extract anywhere from 771 to 1,000 million metric tons of coal, all of which would be shipped overseas to Asia.

Climate Change Impact

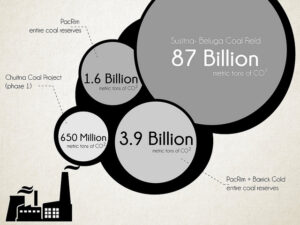

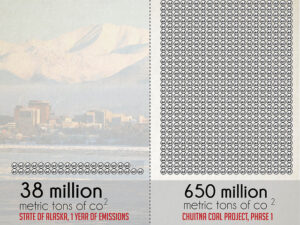

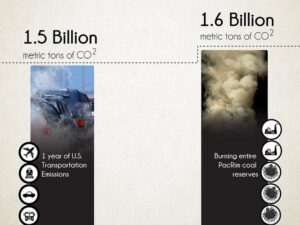

This is where the climate concern gets alarming. The coal from phase 1, alone, will pump 650 million metric tons of CO2 into our atmosphere. The tonnage of CO2 skyrockets to 1.6 billion metric tons when all of PacRim’s leased lands are included. The coal is destined to be burned in factories and energy plants in Asian markets where air pollution and emission controls are the worst on the planet.

This is where the climate concern gets alarming. The coal from phase 1, alone, will pump 650 million metric tons of CO2 into our atmosphere. The tonnage of CO2 skyrockets to 1.6 billion metric tons when all of PacRim’s leased lands are included. The coal is destined to be burned in factories and energy plants in Asian markets where air pollution and emission controls are the worst on the planet.

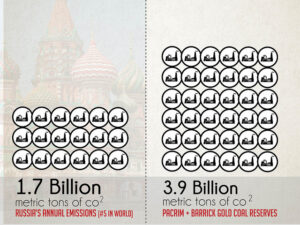

Unfortunately, that isn’t the end of it. Adjacent to PacRim’s leased lands sit lands leased to Barrick, another mining company. Barrick has demonstrated no interest in mining their claims, but with PacRim’s infrastructure in place, they would have easy access to markets and added incentive to mine its leased coal lands. The amount of discharge would more than double to 3.9 billion metric tons of CO2. But what does that all mean? China, a global leader along with the U.S. in greenhouse gas emissions, emits 8.7 billion metric tons of CO2 annually. If this mine proceeds, it would be the equivalent of one-fifth of China’s annual emissions.

It’s Been a Long Fight

Trustees for Alaska has a long history fighting this mine. It dates back to the late 1980s and early 1990s when the project, then referred to as Diamond Shamrock, proposed to mine the coal. Trustees challenged a coal mining permit issued by the State of Alaska and won in court in 1992. The project lay dormant until 2006, when they came back seeking new permits.

Trustees has been working with a coalition of clients including the Chuitna Citizens Coalition, Cook Inletkeeper, and the Sierra Club since 2006 fighting this mine. We have launched a variety of attacks including an effort to get the area designated as unsuitable for coal mining under the coal mining law in Alaska.

We’ve also fought to secure water rights to keep water instream for salmon in Middle Creek. This effort is still underway but we have already been successful in court, winning a court order that forced the agency to address the water rights application. Now we are waiting to hear whether they will give our clients an instream flow water right that would keep water in the creek for salmon.

We are also working closely with our clients to ensure that the best science is on the table and will take all the efforts necessary, including going to court, to ensure that the laws enacted to protect our lands and waters are fully complied with. We have worked year-in and -out on this since 2006 and will continue fighting this environmentally damaging and ill-designed project until it is no more.