On beings and biomes—sea ice is everyone’s business

By Madison Grosvenor

Though frozen, the sea ice biome is anything but still. It endlessly forms and melts, creating a mosaic of ridges, leads, and floes that sustain a vast network of life.

Algae bloom beneath the ice, polar bears traverse the floes in search of food, seals birth their pups on stable ice platforms, and migratory birds rely on ice edges as crucial stopover sites.

What can seem like a static, frozen backdrop is a living, shifting environment.

Spring shorefast ice near Bering Land Bridge Headquarters reaches about a half mile out. Photo courtesy of Bering Land Bridge National Preserve.

The fundamentals of sea ice

Alaska’s sea ice covers stretches of the Arctic Ocean.

Although it can look like one vast blanket of white, it is actually made up of two distinct kinds of ice: fast ice and pack ice.

Fast ice forms when ice becomes firmly attached to the coast or to grounded icebergs and pressure ridges. Because it is anchored in place, fast ice does not drift with wind or ocean currents. It develops each year in the shallow coastal waters of the northern Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort seas.

Within this stable platform, you may find icebergs, older floes, and remnants of multi-year ice. Fast ice is an important seasonal feature for coastal ecosystems and for communities that rely on predictable ice conditions for travel, hunting, and other subsistence activities.

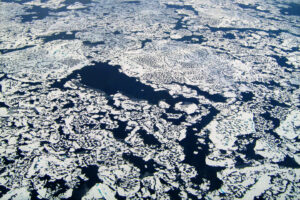

Pack ice in the Beaufort Sea, forms polynyas and leads between floes. Photo by Florian Schulz.

Pack ice behaves very differently. It is not connected to the shore and remains free-floating, constantly pushed and pulled by winds and currents.

This movement prevents it from forming a solid sheet. Instead, it forms a mosaic of ice and open water. As the ice drifts and breaks apart, it forms polynyas, which are open-water areas that persist even in winter, and leads, which are long cracks created when the ice fractures under stress and widens due to wind or current forces.

These features are essential habitats for many Arctic species and serve as important travel corridors for marine mammals.

Even with ongoing changes in the Arctic climate, pack ice remains in the central Arctic Ocean throughout the year, though its extent and seasonal patterns continue to evolve.

Going with the floe

Alaska’s sea ice is a world unto itself, offering refuge, feeding grounds, and the stability needed for entire communities to exist and thrive.

Polar bear scans the water for food along the ice edge. Photo courtesy of NOAA.

Whether related to migratory pathways, hunting grounds, food availability, or resting or breeding sites, relationships between plant and animal species are entirely dictated by the temporal and spatial availability of the ice.

Polar bears are tied to sea ice for nearly everything. In the high arctic, bears travel over ice to access food like seals, whales, and other aquatic mammals.

Polar bears use sea ice as a platform from which to hunt seals. They patiently wait at an air hole, hoping to catch a seal coming up for air or rest. They will also actively stalk seals, or even the occasional beluga whale, from the edge of the ice.

Seal family rests on an ice floe. Photo by Kaitlin Thoreson, NPS.

Seals rely on ice as well. There are four species of seals associated with the ice habitats of the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort seas. These species, collectively known as “ice seals,” include bearded seals, ringed seals, spotted seals, and ribbon seals.

These seals create and maintain breathing holes in the ice by scraping and enlarging the holes with their powerful claws and pushing through the new layers of snow and ice with their noses. This allows them to easily feed below the surface and then come up for air.

Sea ice is an essential haul-out zone for pinnipeds like seals and walruses. Here, they can rest near their food sources.

Breaks in the ice

Just as the presence of sea ice determines where ice-dependent animals thrive, the lack of ice determines how other animals navigate icy regions.

Bowhead whale swims through the blue water towards the ice. Photo by Vicki Beaver, NOAA.

Ice-free leads and polynyas carve migration routes through the ice. Leads, or fractures in sea ice, can act as canals in which narwhals, bowhead whales, and beluga whales travel.

Polynyas act in a similar way, and many species overwinter in these open water areas of pack ice.

Migratory sea ducks, like spectacled eiders, move offshore in the months of October through March, gathering in dense flocks in these polynyas.

These ice-dependent species rely on the water remaining open, for access to food or to minimize the excess energy needed to maintain breathing holes.

Narwhals find a lead within the pack ice, their wintering grounds. Photo courtesy of NOAA.

In some cases, in the high arctic, narwhals have been shown to become entrapped in these leads or polynyas because of the rapidly changing icescape due to high winds or quick dips in temperatures.

When they do become entrapped, many may perish from exhaustion, predation, or suffocation, yet those that survive often do so by exploiting any remaining cracks in the ice, shifting their feeding grounds, or adjusting the timing of their migrations. These behaviors reveal both the limits of their habitual patterns and the flexibility that has allowed them to endure changing conditions.

In an environment where access to open water is a matter of survival, such conditions can shift with little warning. Together, these dynamics reveal a world sculpted by shifting ice and where animals must navigate its every change.

Under the ice

Under the ice, a specialized ecosystem dominated by ice algae and cold-adapted organisms drives much of the region’s marine productivity.

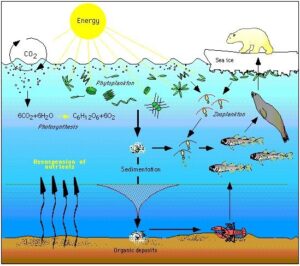

Arctic marine food web. Graphic courtesy of NOAA.

Earlier this year, researchers discovered that sea-ice diatoms, or single-celled algae, can actively glide through the Arctic’s microscopic ice channels at temperatures down to 5 degrees Fahrenheit, revealing remarkable cold-adapted biology. Their unexpected mobility hints that these tiny algae may play a much larger role in moving nutrients and sustaining life within the sea-ice ecosystem.

During late winter, ice algae populate the underside of sea ice. As early spring melting begins, thinner ice and more openings allow more light in and more algae to grow.

In late spring to early summer, as the sea ice continues to melt, algae is released into the sea, becoming a critical food source for a variety of crustaceans and zooplankton. These animals feed the fish and kickstart the entire sea ice food chain.

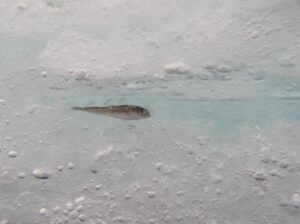

An Arctic Cod rests in an ice-covered space in the Beaufort Sea. Photo by Shawn Harper, NOAA.

Fish, birds, seals, and beluga whales eat one of these fish species, Arctic cod, while seals eat fish under the ice, such as herring, capelin, sand lance, and pollock, as well as octopus and shrimp.

As spring takes shape, the algae-fed plankton sinks to the sea floor and supports communities of clams, amphipods, worms, snails, and mollusks. In turn, these bottom-dwelling populations support large marine mammals such as walruses and bearded seals.

Beneath Alaska’s sea ice, cold-adapted algae quietly drive a food web that supports creatures from plankton to walrus. This finely tuned system linked to sea ice itself is especially vulnerable to the changing climate.

Younger ice is weaker ice

People who study sea ice classify it in terms of age and thickness. New ice starts as a thin layer, less than 10 centimeters thick, formed from frazil crystals that rise to the ocean surface and freeze together. This marks the ocean’s first step towards winter. As it grows past 10 centimeters, it becomes young ice, thickening towards 30 centimeters. Once it surpasses that threshold, it is considered first-year ice: solid enough to last a full winter but still facing long odds of surviving the summer melt-off.

Ice ridges form on the pack ice in the Beaufort Sea. Photo by Harley D. Nygren.

Only ice that holds through summer can become multiyear ice, which can reach 2 to 4 meters in thickness. Multi-year ice is stripped of much of its salt, making it stronger and more buoyant.

This older ice is resilient, but also increasingly scarce. Its survival is a living archive of the polar world and a sign of just how challenging the polar environment has become.

Prior to 2000, the majority of ice in the Arctic was multi-year ice. Now, nearly all of that old ice has melted off.

With thick, long-lasting sea ice gone, shorelines are losing a crucial buffer against storms and waves, leading to faster erosion and more frequent flooding in coastal communities.

Animals (and people) who rely on stable sea ice face shrinking habitat and disrupted feeding patterns. These ecological shifts affect subsistence hunting and food security for Indigenous communities that depend on sea-ice environments.

John Abraham and George Chimugak, Toksook Bay seal hunters, study ice conditions. Photo by Jim Barker.

Indigenous hunters have moved over sea ice since time immemorial. Reliable sea ice has allowed them access to whales and seals as their food and part of their traditional ways of life. But changes in weather patterns and the thickness of ice due to global warming has altered where seals can rest and forced local hunters to travel further to find them.

Hunter Cyrus Harris of Kotzebue, head of the Hunter Support Program at the Maniilaq Association, recounted the difficulty in traversing the changing terrain when interviewed by the Anchorage Daily News.

“We depend on ice thickness and depend on good, safe ice to be traveling on. Without the ice froze, it becomes challenging to get back to shore.”

Generations of knowledge about ice conditions, animal behavior, and safe travel routes have been increasingly unreliable as the environment continues to change.

A warming Arctic shows leads and cracks in the ice cover. Photo courtesy of NASA Earth Observatory.

As multi-year sea ice retreats, darker open water absorbs more solar energy, amplifying warming and accelerating the changes already underway.

As sea ice diminishes, there is no stable environment for algae to grow and reproduce, and so the collapse of the food web begins. With no algae to eat, the zooplankton can’t survive. Without zooplankton, seabirds, bowhead whales, and fish no longer have an adequate food supply. Without abundant fish, seals and walruses are then left without sustenance, and in turn, the polar bears.

With less stable and weaker ice cover, polar bears face longer fasting periods, reduced hunting success, and increased energy expenditure. The loss of sea ice also limits their ability to reach important denning areas, diminishing their survival rates, reproductive success, and overall population size. As a result, polar bears now spend more time on land where they can face more human conflicts.

The last of lasting ice

Winter sea ice cover in the Arctic at its annual peak on March 22, 2025, was the lowest it’s ever been, according to NASA and the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

A 2023 study concluded that the Arctic could see its first ice-free summer as early as the 2030s. Some scientists predict it could be sooner.

This story of sea ice loss may unfold far from most people’s daily lives, but its consequences do not.

The edge of the village of Utgiagvik looks over eroding Arctic tundra bluffs. Sea ice floats in slabs on the Chukchi Sea below. Credit: Lisa Hupp/USFWS.

As the Arctic’s oldest ice disappears, the effects cascade outward, reshaping coastlines, destabilizing ecosystems, and eroding the knowledge and food security of Indigenous communities who know this ice most intimately.

And the impacts ripple far beyond the poles: darker oceans absorb more heat, accelerating global warming; disrupted food webs reverberate through the marine systems that sustain fisheries worldwide; and the altered climate patterns driven by a warming Arctic influence weather, storms, flooding, wildfires, and sea levels everywhere.

The loss of sea ice is not just a polar phenomenon; it’s a planetary one.

This story is not only about loss. Around the world, people are pushing to cut carbon emissions, accelerate renewable energy, and defend vulnerable Arctic habitats — actions that can still temper future warming and help preserve sea ice for generations to come.

Broken sheets of sea ice at sunset. Photo courtesy of USFWS.

We at Trustees for Alaska continue to advance that work by challenging destructive industry projects that would deepen the climate crisis and accelerate sea-ice decline.

By confronting these projects head-on, Trustees works to slow the drivers of Arctic warming and safeguard clean water, natural carbon storage environments like sea ice, and ecological processes that help stabilize the global climate.

The stability of this frozen world is intertwined with our own. In the end, sea ice is everyone’s concern and challenge, its fate inseparable from the future we all share.

This is the eleventh piece in our “Beings and biomes” series. You can find previous articles below:

- On beings and biomes–the wolverine

- On beings and biomes—the boreal forest

- On beings and biomes—keystone and indicator species

- On beings and biomes—a year in the tundra

- On beings and biomes—an intertidal abundance

- On beings and biomes—beluga whales

- On beings and biomes—caribou and their migrations

- On beings and biomes—the perpetual homecoming of migratory birds

- On beings and biomes—wetlands as the center of our everything

- On beings and biomes–eelgrass is the sexiest plant alive