We can repair the climate crisis. Will we?

By Vicki Clark

I want to tell you about a podcast that gets real about the climate crisis. You might say, “Great, another post about climate change telling me about a podcast about climate change. I’ve had enough of the doom and gloom!”

I hear you. The Repair does talk about how we got here, and also how we as humans can take responsibility and make changes that make a meaningful difference in our future. It takes courage and leadership to cure the “human nature” disease leading to “thingification.”

What’s that, you say? Well, let me explain. (If you want to just dive right into the podcast, check out The Repair now.)

First, a short history of humans

The first four episodes of The Repair detail how we humans have organized ourselves in our environment and through our social, religious, philosophical, and governing structures. In the beginning, people knew themselves as part of nature and lived in relationship to it.

As humans created religions, they told stories about how we should be as humans and what our gods or God wanted us to do or expected us to behave. Our relationship with nature, our understanding of ourselves as part of it, started to change.

In Genesis, for example, God said that humans had dominion over the earth and other creatures, and the hierarchy of humans over everything else took root. Soon patriarchy began to assert itself, too.

Groups in different territories fought each other for space and power. People established boundaries, and formed nations and governments. Wealth became something to be acquired as land—and that land in turn was valued for what it could do for people, and most notably those who “owned” it. Soon, the use of or extraction from the land became its “purpose.”

Doctrine of Discovery

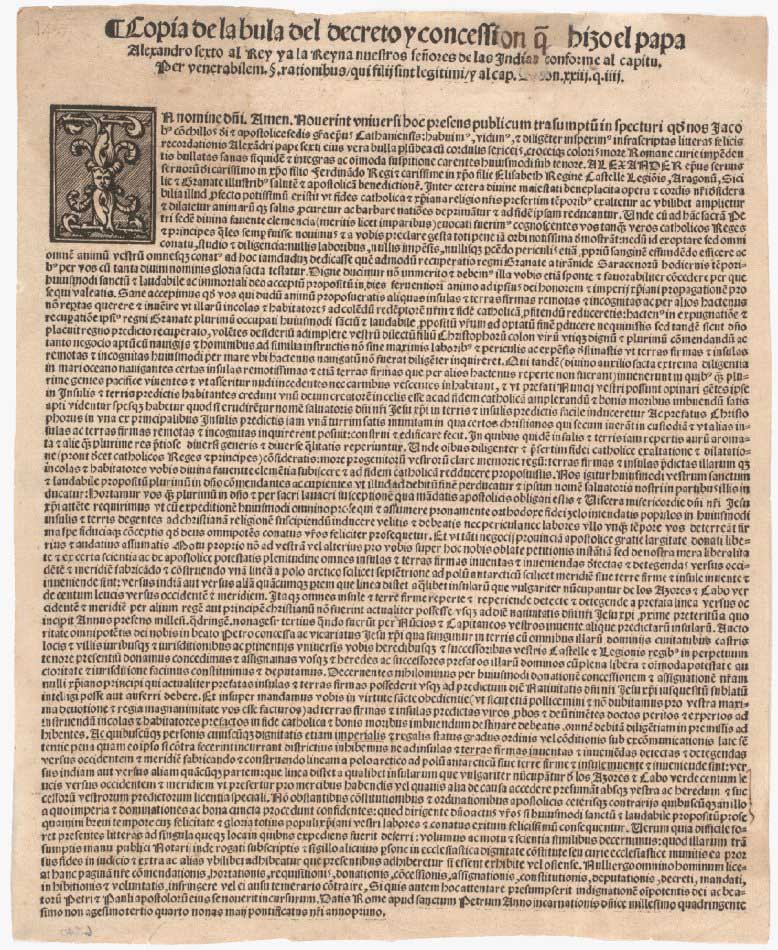

Wealthier nations started looking beyond their borders and settling other lands. Pope Alexander VI issued the Papal Bull “Intera Caetera” in 1493 that established the Doctrine of Discovery, justifying colonization of lands and the enslavement of Indigenous Peoples, and the promotion of Christianity.

During the Enlightenment, human philosophy promoted reason to understand the universe and improve the human condition. John Locke was a central thinker and espoused the “inalienable” natural rights that make individuals equal: life, liberty and property. He famously said, “Government has no other end but the preservation of property.”

Of course, property came to have very broad meaning through colonization and the enslavement of people. Free labor built more wealth and made the land more valuable. In 1955, Amié Césaire, a poet and politician from Martinique, wrote the essay Discourse on Colonialism. In it, he says that colonization dehumanizes people and results in “thingification,” wherein people become things or objects that can be used or discarded.

This is exactly what happened in the genocide of Indigenous Peoples and the enslaving of Black people.

Industrialization as the extension of dominion and “thingification”

In the early 1900s, the titans of U.S. industry extracted coal and oil, and also the labor of workers who toiled long hours in unsafe conditions for low wages. As the labor movement began to rise and public sentiment began to turn against industry, a new industry bloomed: public relations.

Soon, the “spin” made extraction and its products as essential to America and American life, and framed big business as heroes of democracy and American values.

In Roland Marchand’s 1998 book, “Creating the Corporate Soul: The Rise of Public Relations and Corporate Imagery in American Big Business,” he said that “public relations is charged with a mission to invest corporations with a soul.”

I guess you could say they succeeded when the U.S. Supreme Court gave corporations individual rights.

The podcast covers a lot of history and how various forces got us to the climate crisis. Though humans are part of nature, we have sought through time to have “dominion” over it and to “thingify” other humans, animals, and the land itself to gain more wealth and power.

We’re now confronting the climate crisis because of the choices of people with power, and the ever-increasing desire to consume goods.

What people in other places can teach us

As the podcast unfolds, we learn about countries that have contributed little to the climate crisis and yet experience big impacts and/or need to find immediate solutions.

Indonesia is prosperous and part of the G20. For the capital Jakarta, however, climate change means rising sea levels that threaten the largest city. A huge seawall project would help mitigate the problem, but would cost $100 billion. Would the Netherlands—a country that enriched itself by colonizing Indonesia—offer to help? Not even a fraction of a percent. In Nigeria, violent clashes between farmers and nomadic herders in the “bread basket” of the country have become an untenable situation. On the coast, horrible flooding is taking out homes. Yet, realtors continue to sell properties likely to flood! The Niger River delta, which was exploited by Royal Dutch Shell is one of the most polluted places in the world.

Bangladesh is one of the developing countries hit hardest by climate change. Storms and flooding have made Bangladeshis refugees in their own country. Some clothing companies have invested in LEED-certified buildings and better working conditions, but the government’s moves to have economic growth is nowhere near what is needed to address impacts. When climate activists discuss climate reparations, it has been determined that $100 billion/year is needed. Bangladesh desperately needs help. Will its former colonizer the Netherlands help? Not nearly enough.

Scotland has a history of oil drilling off the coast of the village of Nigg. The people benefited economically from those jobs, but they didn’t last forever. The port is now becoming part of a renewable energy future.

In some countries, people have asserted the “rights of nature” in law and in court. The law in Ecuador now views nature as having a right to thrive. In New Zealand, a law was passed protecting ecosystems. A few states in the U.S. are also passing laws with a right to a healthy environment.

Where do we go from here?

So, what are the solutions? The final two episodes of the podcast look at what we can do to change course.

The penultimate (I love that word) episode discusses policy options. A note about policy is that the U.S. executive and legislative branches are separately elected unlike other constitutional republics that elect one party. This makes it difficult to get on and stay on a path to make the changes required to address the climate crisis.

People must do what they can, but governments need to do much more. To keep warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius—which is becoming less attainable every day—we need to globally decrease emissions by 8-12 percent per year.

Policies need to work toward care and repair, such as:

- Curb methane emissions because methane is a super greenhouse gas even though it has a shorter life in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. In doing that, natural gas cannot be a “bridge fuel,” at least not for long

- Stop subsidizing fossil fuels. Globally, these subsidies amount to $5.9 TRILLION, while oil companies make huge profits!

- Utilities can be a big factor in moving generation facilities to renewable sources.

- Lawsuits are challenging bad policies and attempting to hold industry accountable and they are slowly moving through the court systems.

- Folks are discussing nuclear energy, which is controversial. But taking nuclear offline and moving to fossil fuels does not help.

- Stop “disaster capitalism”—the practice of taking advantage of a major disaster to adopt less regulation and more liberal economic policies than would be accepted under normal circumstances. Private interests also descend after disasters to buy cheap land and convert it for profit and take advantage of government money.

- Carbon capture and sequestration is discussed, but not yet viable. Pulling CO2 out of the air isn’t an option. Pumping gas into reservoirs to increase pressure for more oil extraction also defeats the purpose.

We need big change

As we can see in these policies, it would be difficult to pass and implement them, especially if decision makers continue in the mindset of capitalism, wealth, power, and property. Our society’s operating systems lean toward propping up ideas of liberty and private property rights—and those who profit from related policies—rather than on systems that prioritze human equality and collective well-being.

But is “human nature” what keeps us here? I don’t think so. As Ursula K. Leguin said, “Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings.”

We need to change our thinking about economics. We measure how we are doing by GDP, Gross Domestic Product—transactions of goods and services. And the goal is constant growth, which if you think about it is impossible. It’s a mindset of constant scarcity.

What is left out are the values of what are called intangibles—what nature provides, happiness, health, a safe place to live. These are not captured in the way we now think about the world, where a 3,000-year-old sequoia has no monetary value standing in the forest helping the planet breathe, yet can be sold as lumber for a pittance.

Some economists are developing economics for the common good. This movement puts the common good, cooperation, and community up front.

There is also what might be called “original culture”—how humans related to the land and other living things in the beginning. Treating the earth, critters, plants, waters, and lands as partners in a relationship of give and take—not just take. It is taking the perspective of an ancestor to those who come after us and part of the knowledge and wisdom passed from generation to generation.

Everything on this planet is connected and we can no longer “thingify” Mother Nature and other humans. If we don’t resist the status quo and make the big changes necessary for health and future generations, we only have ourselves to blame.