Why I want to swim with whales. Alaska News Brief July

Talking about the weather isn’t chitchat anymore.

When wildfires turn the sky apocalyptic orange hundreds of miles away, when floods turn city infrastructure to rubble, when heat makes walking outside lethal, it isn’t filler conversation—it is THE conversation.

The climate crisis predictions we’ve heard and shared for decades now show up in our daily news feeds and at our front doors. Part of me wants to complain about how the long gray snowy spring in Anchorage rolled into a rainy gray June—and now July—but my weather complaints are the tip of a nearly melted iceberg spreading calamitous climate consequences to all.

Heat domes. Thousand-year floods. Relentless and destructive hurricane seasons. The coupling of climate change with complex systems of ocean and atmospheric currents. It all feels so terribly out of our control. And for the most part, it is.

Yet, Exxon knew over fifty years ago what today would look like, and so did many others—the oil and gas industry predicted and then denied it, world leaders knew of and ignored it, decision-makers learned about and waved it off. Even as climate destruction happens in front of our eyes, industry keeps selling its snake oil while political, economic, and power interests continue demanding their cut.

Many, many, many people predicted that churning out greenhouse gases would hurt people. They saw something and said something.

Yet, systems of power that actually could do something did little or nothing. Societies failed to do what’s necessary to head off dire outcomes or do what it takes to usher in better ones. Thinking and caring about consequences could be the most “human” act of being, and yet these human systems failed at an essential survival strategy.

Talking about the weather makes it hard to pull out of a bad mood. Thinking about the weather makes it hard to feel empowered. Calling it the “new normal” makes it difficult to feel hope.

This is where sperm whales come in; when I feel disheartened, frustrated, angry at our species, I want to hang out with whales—the sperm whales of Dominica to be exact. Here’s why.

Sperm whales have the biggest brains on earth and the loudest voices. If we could fully hear them, our ear drums would probably burst. Possibly even vibrate you to death. They live in deeply connected family groups. They stick close together and talk all the time. Baby whales can’t dive deep, so when it’s time for its mother to forage and hunt, a caretaker will protect the young whale from orcas and other dangers.

Whales talk the entire time. They are in constant communication so they can support each other. And when danger comes, nearby families will come with reinforcements.

Their relationships and way of caring for each other inspires me. I don’t know if I will or should swim with the whales of Dominica, but the small island nourishes a few hundred of them year-round. There are consequences when human beings push themselves into the worlds of more-than-human beings, and also, we have always had relationships and encounters with the animals around us. Some good and sustaining, some not.

Whales have their lives, their expectations, their ways of living. In “Becoming Wild: How Animal Cultures Raise Families, Create Beauty, and Achieve Peace,” Carl Safina talks about the traditions and knowledge passed between animals like sperm whales.

Certainly, the commercial whaling system taught many whales to be wary of human beings and their structures, and those lessons passed to future generations. Generations of whales carried that knowledge and trauma. What happens, though, when people rebuild trusting, caring, respectful relationships with these animals?

What could these whales tell us about the weather in the oceans, the changes they’ve experienced, the patterns they’ve seen? What wisdom would they share about consequences and action, and hope and love, if only we could understand them? If only we would listen?

That’s why I want to hang out with Dominica sperm whales sometime this next year. I can’t dive deep like they can, nor speak in their sonar codas, but I can learn from them, recalibrate my mood, center my values, learn to communicate in ways that help us all support each other. I can remember my role, my relationship, my power.

Sound travels far in the water. Years ago, in Hawaii, I heard a humpback whale sing a song that resonated so profoundly that I was convinced the whale was right there—behind, below, beside, or above me—but I never saw that whale.

They had shared their most precious gift, though, and I swam through the song of their wisdom.

PS. Thanks to supporters like you, we can continue fighting to protect Alaska’s land, water, air, wildlife and people.

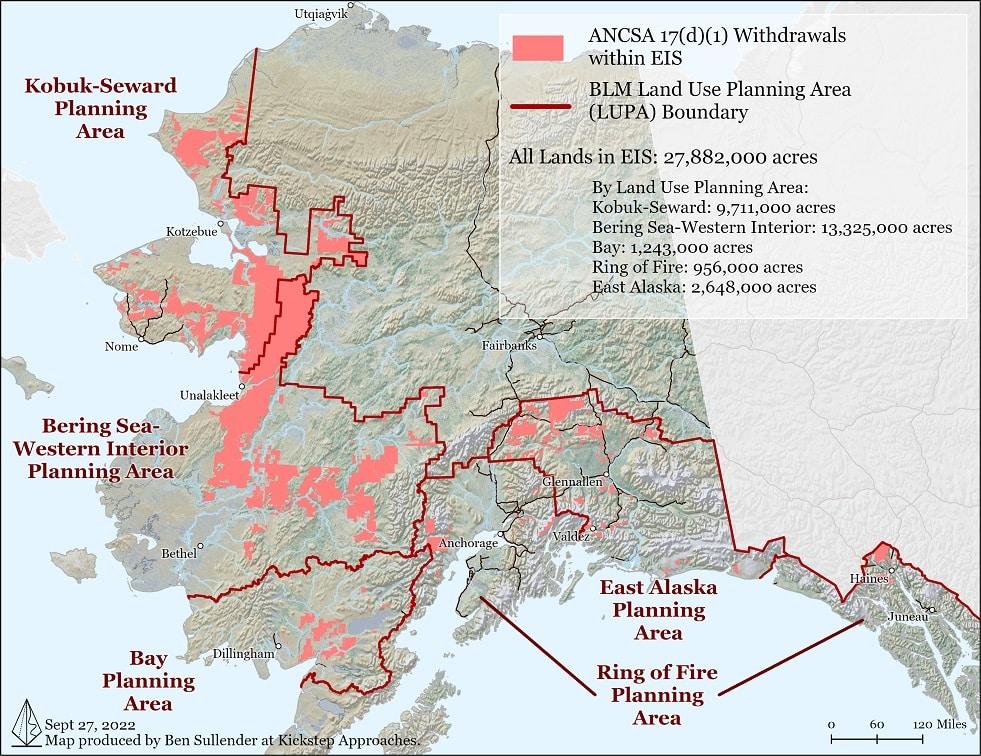

What are D1 lands and why should you care about them

Drinks with lawyers–Rachel makes the case for shiny red shoes