Drinks with devo – Tracy makes good choices

By Dawnell Smith

Tracy Lohman grew up in a blue-collar neighborhood steeped in steel mill culture and working-class values. Her dad worked for International Harvester for decades. When the steel industry tanked and pulled his job down with it, he started his own business fixing equipment. None of it came easy. Tracy grew up knowing that hard work and scrappiness were necessary attributes.

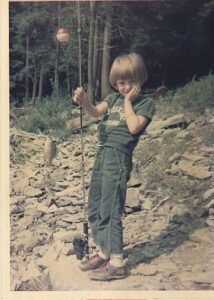

Tracy’s first fish. Photo by Ed Walczak.

She also grew up near Pittsburgh—once called “The City of Smoke”—after a century-long industrial free-for-all. She remembers as a small child in 1970 watching the steel mill smokestacks as her family drove through the industrial district to a Pittsburgh best amusement park. She wondered what all the factories were making. Pollution?

As a child, she didn’t have a vision for what she wanted to be when she grew up, not specifically, but she recalls being pulled toward a larger world, to other possibilities. These days she can’t say how dreaming of seeing the world grew into a lifelong career of bringing resources to nonprofits, but that’s the path she took.

“It’s not quite something that one plans,” she said.

For the people who knew her back then, it all makes sense. Her cousin Lynnann Hitchens spent a lot of time with Tracy when they were kids. They grew up in neighboring communities and celebrated birthdays and holidays together. They hung out during swim parties, picnics, slumber parties and family get togethers over Steelers football games.

“Tracy was always a sensitive and caring person, good natured and fun, enthusiastic, friendly, outgoing and ready for anything,” said Lynnann. “She had many friends, and whether it was playing outside with friends, at a family event or party, her infectious and distinctive laugh always filled the room. It’s easy to believe that she uses all these traits to engage donors and lead fundraising efforts. She possesses the key characteristics that are needed to pull people together—especially around an important cause.”

The best medicine

Tracy can find hilarity even during the worst situations. She can carry a witty theme forward for months, and she laughs heartily at other people’s one-liners and stories. Laughter is good medicine, and so is connection. Tracy reaches out with generosity and kindness when others face hardship. She listens to people and asks questions with a genuine interest in their answers. She says what she thinks, too, and sometimes says too much, and then laughs about that as well.

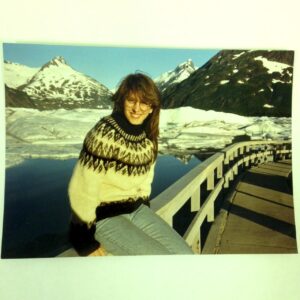

Tracy with Portage glacier behind her, back when you could see it from the parking lot, 1990.

Her friend Lisa Gill says Tracy was the first person she met after moving to Alaska.

“We have been adventure partners, book group buddies, foodie companions, concert goers, and dear friends through both the routine and extraordinary for the last 30 plus years,” said Lisa. “The first thing anyone notices about Tracy is her bright smile and the infectious laugh that she brings to any new adventure, whether hiking through soaking rain in Katmai’s Valley of 10,000 Smokes, paddling Alaska’s rivers or lake systems, driving the Alcan, and in simple gatherings of friendship.”

Her uncle Rich Walczak described her as “a sweet, friendly outdoorsy little girl” who made friends easily and had a big vocabulary when very young. She loved camping and fishing, he said, and her family always had animals like beagles, guinea pigs and a chameleon.

He believes Tracy got her love of animals from her mother, who wouldn’t hurt a fly. Tracy’s dad was a hunter, so her parents had to agree to a family truce.

It’s true that Tracy talks to animals. Every day she says something to or about birds, the beauty of the unappreciated starling, the moose at her door, the bees and insects that whirl about as she gardens, the office dogs, all the kitties that need homes, the reptile she’s recently fallen for while taking care of it for a friend.

She likes getting her hands dirty—and her feet, too. Her cousin Lynnann says they were always around dirt as kids. They hung out with their grandmother, who had flowers, vegetables, trees and other plants in a small urban yard, along with a compost pile and rain barrel.

“Tracy and her family loved nature and the outdoors and were often camping and fishing,” she said. “Our families valued the environment and did not take it for granted. Tracy knows the importance of conservation and environmental protection—especially when you come from a place where you can see, firsthand, the effects of industrial air pollution and rivers too polluted for fishing or swimming.”

A family photo from 1976. Courtesy of Tracy

There’s a through line, here. The child who wanted to see the world, who had a love of animals and being outside, had an awareness of what “outside” feels like when unhealthy. Her path from a steel town to Alaska and Trustees for Alaska seems inevitable in hindsight, but it could have taken her in many directions.

J is for Japan

In college at Slippery Rock University in the late 1980s, Tracy took classes in French, Spanish and Japanese while working toward a communications degree. It was a difficult time for her family, as her dad transitioned to trying to make a living with his own business. Tracy had to think about making a living, too.

Her impulse to see new places got her thinking about jobs and careers that involved travel, but she didn’t want to work for an airline or the travel industry. She joined a three-month study abroad program that took her to Japan in 1988.

Instead of leaving after three months, she choose to stay and take some money-making gigs. She taught English and French, worked for an ad agency, and even did a stint as a magician’s assistant. (Don’t ask her to pull a rabbit out a hat, though she will pull a name out of a bucket every month during our 50th anniversary monthly donor drawings all year!)

When she returned home, she felt lost, even as the next job search began. She first looked into study abroad programs that would have administration positions, but she eventually started “going through the Yellow Pages starting with the letter ‘J’ for Japan,” she said.

She found the Japan America Student Conference and made a cold call. The person who answered asked her to come to the organization’s small Washington, D.C. office to meet with them. They weren’t really hiring, but they decided to create a part-time position. She went to the office two times a week and augmented her income by working as a nanny for a Japanese family.

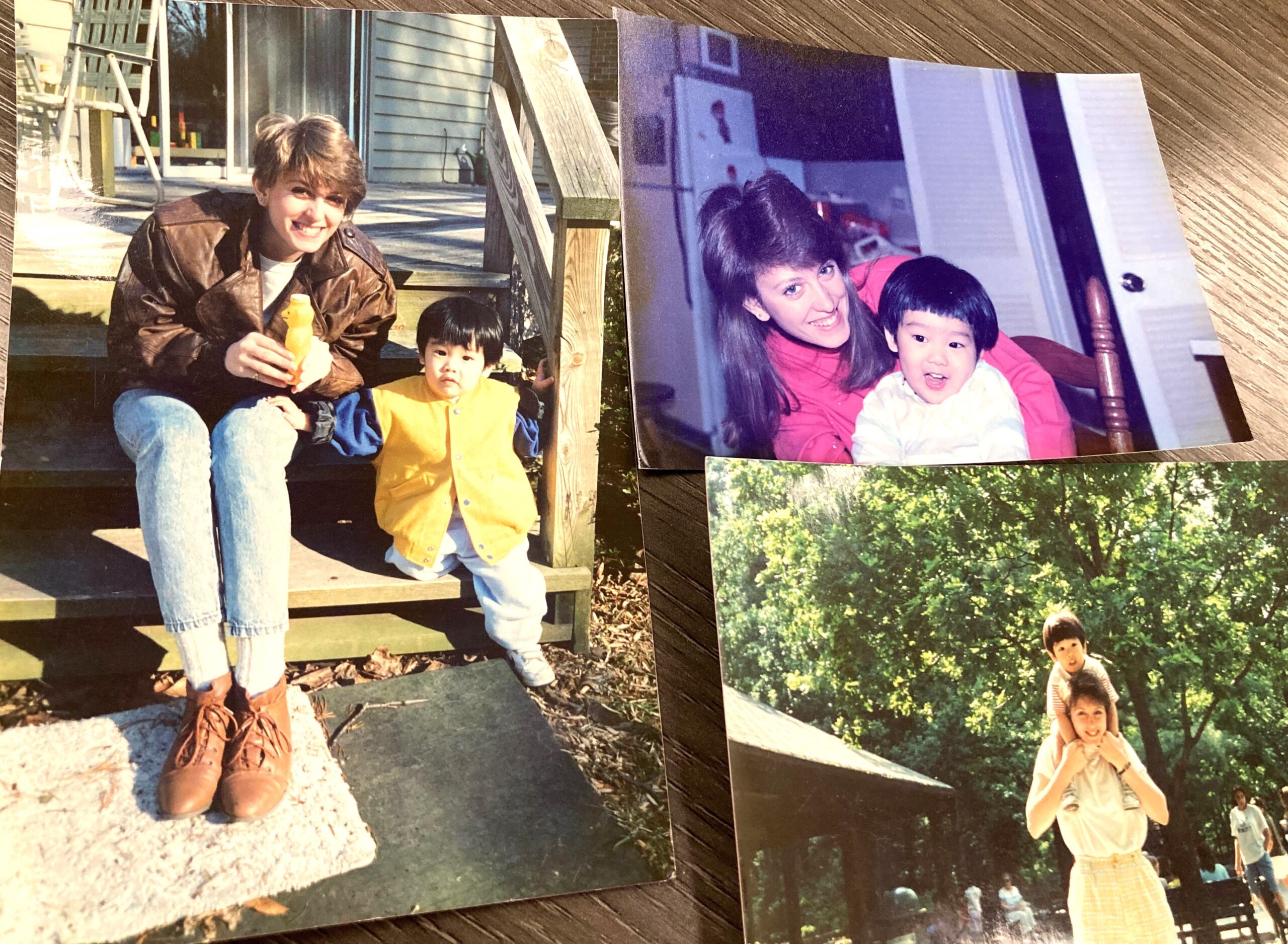

Photos of Tracy with friend while in her nanny role in D.C.

“They gave me room and board, $600 a month, and I ate home-cooked Japanese meals every day,” she said. “Who would complain about that?”

The executive director left nine months later, and they offered the job to Tracy with an annual salary of a whopping $18,000 to make ends meet in D.C. These days Tracy wishes she realized back then how cool it was to work in a historical building and live two blocks away in the Foggy Bottom district while 22 years old and being sent to organizations and businesses like the Japan and Subaru foundations to ask for money.

She had no experience in fundraising or running an overseas exchange program, yet there she was, doing it. It was a crash course in development work.

“I learned on the fly by just telling the story of the organization,” she said. “The rest just happened. You just tell people about the program’s goals and impacts, what the program needs in order to make it happen and the fear vanishes. I was so young, but I knew the story and could tell it.”

After the oil spill

The job’s focus centered on bringing together 40 students from Japan and 40 students from the United States. It meant doing all the planning and logistics, and facilitating decisions. The students set the itinerary and curriculum and she supported them. In her first trip with students, the group met in Japan in 1989, right after the Exxon Valdez oil spill. For the next trip, students chose Alaska.

“My immediate response was no way, we can’t afford taking 80 students to Alaska!” she said. “But they really wanted to go and gain first-hand knowledge about the environmental impacts. So, the fundraising efforts began.”

To make it happen, she did a preliminary trip in 1990 to lay the groundwork and do some fundraising. She met with Ted Stevens, then a storied Alaska senator, and with the mayor of Anchora

Group photo of the students participating in the Japan American Conference.

ge, Tom Fink. She visited the Japanese consulate. (Of note, she also met a guy, but that’s another story.)

She returned in August 1990 with 80 students. They spent ten days visiting Alaska, holding a debate between folks with Exxon and folks with the Alaska Center for the Environment, and spending a lot of time seeing and talking about the water and animals.

She said that years before that trip, when in college, she did a project with another student who said his big plan was going to Alaska, and “I thought that was crazy. Then I ended up coming here and just being awed. After that Japan America conference, I said to myself, ‘I’m moving to Alaska.’”

She took a leap of faith and moved to Alaska in late 1990. Another job search began. Turns out, Trustees for Alaska needed a temporary office manager.

Make good choices

That short stint with Trustees led to a series of jobs with nonprofits, which fit her goal of working for nonprofit or international organizations. She worked for Alaska Geographic doing administration work, then for Alaska Community Share as executive director for 5 or 6 years, where she cut her teeth in funding work. She moved to the Alaska Marine Conservation Council as office manager and later the manager of fundraising and member stewardship, and then back to Trustees as office manager a second time. She took positions with YWCA, and then for the ACLU, and returned to Trustees for Alaska the third time in 2016 as development director, where she intends to finish her career.

Tracy with her garden friends.

She liked a lot about these positions, including the people, the purpose, and her ability to do her part to support the work. She also experienced the challenges of working for nonprofits facing hardships, like having too little money, losing funders, embezzlement, and work environments that felt on the edge.

As with most people, those rough work environments can take a toll. The thing about Tracy is that she thrives in an environment where laughter is robust and conversations open. When she talks to people, she brings her whole heart, and when talking to people on behalf of Trustees, she also has a job to do. Her husband Tom Lohman says the pressure is real.

“With the powerful opponents the organization typically faces, the financial margins are slim, and there is always a need to raise ever more money,” he said. “It takes a particular focus to face that challenge every day. On the one hand, Tracy’s ability to connect with people and form lasting relationships with donors is essential to her success. On the other hand, she is keenly aware that Trustees must compete among a legion of worthy nonprofits for a finite pool of funding. Her nonprofit work causes her to see imbalances between the powerful and those looking to challenge that power.”

The way Tracy sees it, whatever the pressure to hit financial goals, her fundamental role is a human one. She fosters relationships, maintains transparency, makes it clear that the organization cares and values its donors as partners in the work, and gives people her attention.

There’s inevitably an “ask” or request for a donation in many of her conversations. Sometimes it’s the first ask, other times it’s an ask for a larger gift or monthly donation, or inclusion in someone’s planned giving, the hardest ask of all.

“We all know we die, but it’s so hard to talk about,” Tracy said. “I’m more comfortable talking to people about it now than I was before. A lot of people don’t even think about it, but should talk about what they want to have happen with their money behind when they die.”

There’s an emotional weight to asking for donations, and mishaps happen along the way, like misreading how much someone feels comfortable donating, or feeling horribly awkward while waiting for their response.

In a way, all the tasks that go with Tracy’s work give her space to process that emotion. You can find her fussing with graphics, stuffing envelopes with thank you cards, organizing food for an event, chatting with board members about the next appeal letter, even lovingly tending to the gecko in a colleague’s office.

It all fits for her—the people, conversations, animals, oceans, mountains, birds at the feeder, cats at the window.

Tracy’s friend Lisa said that Tracy “has demonstrated a life-long passion for protecting the environment that is evident in her work, her family life, how she has raised her boys, traveled the world, and through volunteer projects. That passion has provided a consistent compass that connects everything about her.”

That kid from Pennsylvania may not have known she wanted to grow up to be a development director, but she dreamed of seeing the world and doing something unconventional, something with tremendous meaning.

“It’s the talking to people that I love best,” she said. “It gives me so much joy and energy to listen to them, to know the work we’re doing matters. I feel so good about what I do and the choices I made.”

This is the eight in a series of profiles based on interviews with Trustees’ staff over drinks, this time over cocktails at the Speakeasy at Williwaw in Anchorage.

More in the “drinks with lawyers” series: