You searched for arctic refuge

-1

search,search-results,paged,paged-2,search-paged-2,bridge-core-3.3.1,qode-page-transition-enabled,ajax_fade,page_not_loaded,,qode-title-hidden,qode-child-theme-ver-1.0.0,qode-theme-ver-30.8.1,qode-theme-bridge,wpb-js-composer js-comp-ver-7.9,vc_responsive

Arctic Refuge Threatened Again: Alaska Brief Newsletter – July 2014

Dear Supporter: Once again, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is under threat....Trustees Works to Protect the Coastal Plain of the Arctic Refuge

Trustees for Alaska is going to court once again to protect the...What’s the Izembek Refuge land swap and road proposal really about?

By Dawnell Smith In the early 1980s and for decades after, Alaska...Do Interior’s latest actions mean the Arctic is finally protected? Not yet. The devil is in the details.

The Biden administration did several things earlier this month that could lead to enduring protections for the Arctic and potentially make meaningful headway on climate change. First, the Interior Department cancelled the last remaining oil leases stemming from the reckless Trump-era lease sale for the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.A month in the life of protecting the Arctic

We won in court and are still in court to protect Alaska's Arctic region. Learn about upcoming comment periods by signing up for our newsletter.A long walk in the Arctic

Late last June, I drove from my home in Anchorage to Fairbanks to join a group of folks for a backpacking trip in the western Arctic. The next morning, we jumped into a mail plane to the village of Anaktuvuk Pass, poised between the Anaktuvuk and John rivers within the Central Brooks Range. It was a bumpy and spectacular ride. The wind blew hard and cold in late June, so we bundled up after landing.The Arctic on the precipice

By Dawnell Smith Alaska faces serious climate impacts, pollution concerns, and industrial...An Arctic wish list with 2022 resolve

Our work feels less frantic and chaotic than it did a year ago. Nonetheless, the divisive 2020 election that led to an insurrection slashed any hope of taking a break from staying vigilant about defending democracy, ensuring climate action, and sustaining the health of Alaska’s lands and waters. Yes, a lot has changed in 2021, with real hope that climate policy will honor and prioritize frontline communities and Indigenous ways of life. Yet the Biden administration continues to defend Trump era decisions and actions that threaten Alaska communities, animals, and landscapes.The good news, and the bad, for Alaska’s Arctic

While the Biden administration promises climate action and clean energy, and Alaska’s political leaders spout the “drill baby drill” mantra of fossil fuel dinosaurs, Alaskans and people around the world face enduring threats to their health, ways of life, and homes at the hands of industrialization and climate chaos. Now there's more good bad news for Alaska's Arctic.Shining light on the Arctic

Despite four years of intense arm-twisting by political players and industry insiders to put drilling rigs on the sacred calving grounds of the Porcupine caribou herd in the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, there are no rigs. Protected areas in the western Arctic also remain mostly unscathed, despite hasty attempts to push project and management plan approvals through processes devoid of scientific integrity or compliance with the law.Join us in the Arctic!

We decided to host two trips to the Arctic this year to...Alaska’s largest Arctic lake threatened

The Trump administration intends to undermine protections to public lands vital to...Interior disregards human rights in rush to lease Refuge

Officials from the Interior Department set up meetings in Kaktovik, Utgiagvik, Fairbanks...Climate change puts Arctic communities in peril

Whether living in the Arctic or an urban center in the Lower...Feds put pristine Arctic at risk

America's Arctic is at risk.Litigation 101: What does it mean to intervene?

What does it mean to intervene in a lawsuit? Let's use our recent legal action to protect the Arctic Refuge to explain.Act now

The Arctic Refuge Defense campaign includes an array of Alaska and national groups working together to protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. When signing the petition, you join a movement of Alaskans and Americans protecting sacred and public lands, wildlife and wildlife habitat, food access and public health, and the health and integrity of natural places. Sign on to be heard and learn how you can take action to protect the Arctic.Alaska Brief Newsletter – March 2016

The March 2016 issue of the Alaska Brief includes: a story from a supporter about his trip to the Arctic Refuge inspired by his 40-year friendship with Mardy Murie, how the State of Alaska fails to get it right in oil and gas leasing, and the Healy Coal Plant fire.2015 Conservation Victories: The Year in Review

23 Dec, 2015

in America's Arctic, Clean Air and Water, Climate Change, Marine Ecosystems, News, Wild Lands & Wildlife

Trustees for Alaska achieved many victories for conservation during 2015 including protection of the Arctic Refuge, Pebble permits ruled unconstitutional, predators protected, and many more.

in America's Arctic, Clean Air and Water, Climate Change, Marine Ecosystems, News, Wild Lands & Wildlife

Alaska Brief Newsletter – July 2015

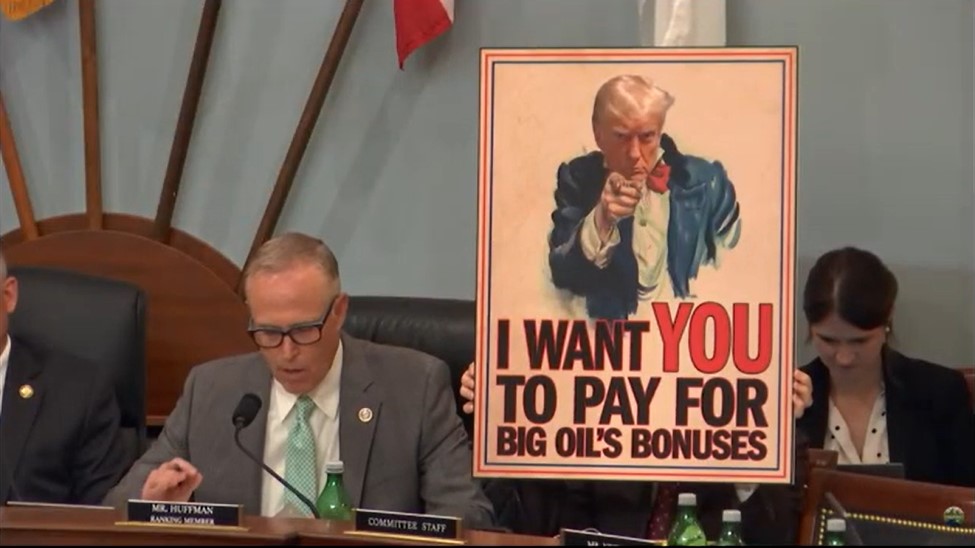

The July 2015 issue of the Alaska Brief, Trustees for Alaska's monthly electronic newsletter. In this issue: Water Quality, Bombing at Eagle River Flats and Arctic Refuge Trip.A brutally dangerous budget bill and how you can help stop it

By Dawnell Smith Congress is misusing a budget process to try to...On beings and biomes—a year in the tundra

By Madison Grosvenor Alaska’s tundra is a land of extremes, where life...Press Releases: 2025

25 Mar, 2025

in

2025 Press Releases March 25, 2025: Court ruling lets AIDEA keep Arctic...

in

How to focus on Fridays

By Madison Grosvenor If you’ve seen Trustees on social media over the...Our response to the Trump administration’s industrialization agenda in Alaska

The Trump administration released a rash of executive orders on Jan. 20....Alaska News Brief January 2025–Hello, 2025. We’re ready for you.

Throughout 2024, we threw parties and shared funny and true stories about...The 50th Anniversary series: Landmark cases

20 Dec, 2024

in 50th anniversary, America's Arctic, Bristol Bay, Clean Air and Water, Wild Lands & Wildlife

By Dawnell Smith A winning lawsuit can set the stage for legal...

in 50th anniversary, America's Arctic, Bristol Bay, Clean Air and Water, Wild Lands & Wildlife